Many Māori and others have submitted the DNA samples via web sites such as Ancestory.com and 23andMe to ascertain their whakapapa, many without realising the cultural and privacy issues of doing so. Most often, you are giving away your rights to your own DNA that has all of your information about you and your ancestors.

From a Te Ao Māori perspective, this is your biological whakapapa of your entire generation, your whānau’s future generations and of all of your tipuna.

Whakapapa of DNA

Here is one perspective of a DNA from a Māori person. It is taken from my PhD thesis “Māori Genetic Data – Inalienable Rights and Tikanga Sovereignty” which focused on these issues from a Te Ao Māori perspective and found that there were no Te Ao Māori guidelines for Māori, there are still not others to date.

Scientists and genetic researchers may also find my publication useful “Tikanga Tawhito Tikanga Hou – Tikanga Associated with Biological Samples.”. A bioethics guideline that explores the ethical storage and research of Māori genetic samples.

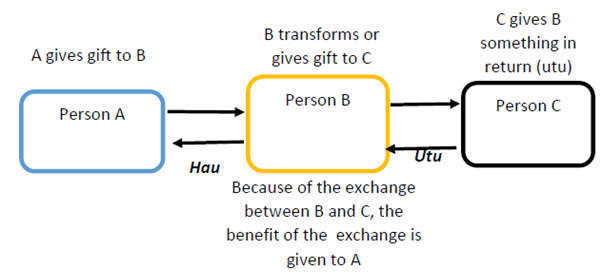

From the top, all Māori descend from the beginning of time. For some Māori and Iwi that is s supreme being called Io. For others it may be from Te Kore. There are other variations of creation stories among Iwi and hapū. For example my thesis has a much different form from Ngāi Tahu.

For many Māori, there are the atua (deities) Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (earth mother) who had 70 plus children. Among them was Tāne Māhuta who created the first woman Hine Ahuone, who had multiple children (Atua). In the physical world we have marae where we descend to a tipuna who is the lead of an iwi. An Iwi is a collective of hapū and whānau. The whānau is made up of individuals.

It is argued that a DNA sample from a Māori individual must consider the wider perspectives of the whānau as the DNA links the individual back and forward in their genealogy. Things like diseases, diets, health risks and an ever growing list of traits that contain our most unique privacy details.

DNA Tests

It has become an almost social trend to take a DNA test to find out who we are. While there is not currently a specific Māori gene to identity Māori, we can identify relatives who are Māori, noting this requires checking your genealogy to see if you are also Māori as opposed to having a Māori relative.

23andMe recently confirmed hackers stole DNA data of 6.9 million users. It also recently parted ways with all its board members, its stock is on the verge of being delisted, it shut down its in-house drug-development unit last month, numerous rounds of staff layoffs. Amid these issues, it announced they are considering selling 23andMe—which means the DNA of 23andMe’s 15 million customers would be up for sale, too.

23andMe’s privacy policy stipulates, “If we are involved in a bankruptcy, merger, acquisition, reorganization, or sale of assets, your Personal Information may be accessed, sold or transferred as part of that transaction… We may also disclose Personal Information about you to our corporate affiliates to help operate our services and our affiliates’ services.”

The New Zealand Herald article wrote about stating New Zealanders are concerned their genetic information could be on-sold and used for other purposes, including insurance or law enforcement and quoted New Zealand Privacy lawyer Rick Shera:

“But at the end of the day, you can change your driver’s licence, you can change your credit card, you can change your passwords and so on. You can’t change your DNA.”

The degree to which you have control over the genetic information you’ve submitted, and even your physical DNA sample, “varies widely, depending on the company, according to published research on the privacy policies of genetic testing companies.

Last year, for example, 23andMe extended a deal to share its genetic databases with pharmaceutical company GSK, which agreed to license the data for drug development for $20 million. Meanwhile, the advocacy group Color of Change has called on 23andMe to stop profiting off of the genetic data of its Black customers, who may use DTC genetic testing services because the U.S.’ history of enslavement makes information on genealogy otherwise difficult to find for Black families.

As long as DNA testing company terms of service don’t specifically prohibit it, these companies can conduct research on your genetic data, sell it, or share it with third parties. There’s a real risk that somewhere along the way, this information could be used in ways that are harmful to the person who submitted their data for testing or even to their whānau.

The once hypothesised worst-case scenario is now increasingly becoming a normal where, “a health insurance company might find you have a predisposition to develop early onset Alzheimer’s, cancer, mental illness, or substance use disorder, and discriminate against you based on that,”, especially if you have submitted your DNA to a testing company.

This message from Meredith Whittaker is a warning to all Māori who have done a DNA test.

“It’s not just you. If anyone in your family gave their DNA to 23&Me, for all of your sakes, close your/their account now,” Meredith Whittaker, president of the encrypted messaging platform Signal, posted on X after the board’s resignation.

Deleting your Data

If you are concerned about your data and live outside of New Zealand, you could use the app from https://permissionslipcr.com/

Otherwise the following instructions were correct at the time of writting.

23andMe

- Log into your account and navigate to Settings.

- Under Settings, scroll to the section titled 23andMe data. Select View.

- You may be asked to enter your date of birth for extra security.

- In the next section, you’ll be asked which, if any, personal data you’d like to download from the company (onto a personal, not public, computer). Once you’re finished, scroll to the bottom and select Permanently delete data.

- You should then receive an email from 23andMe detailing its account deletion policy and requesting that you confirm your request. Once you confirm you’d like your data to be deleted, the deletion will begin automatically and you’ll immediately lose access to your account.

Genetic sample

When you set up your 23andMe account, you’re given the option either to have your saliva sample securely destroyed or to have it stored for future testing. If you’ve previously opted to store your sample but now want to delete your 23andMe account, the company says, it will destroy the sample for you as part of the account deletion process.

Download your raw genetic data

- Navigate directly to you.23andme.com/tools/data/.

- Click on your profile name on the top right-hand corner. Then select Resources from the menu.

- Select Browse raw genotyping data and then Download.

- Visit Account settings and click on View under 23andMe data.

- Enter your date of birth for security purposes.

- Tick the box indicating that you understand the limitations and risks associated with uploading your information to third-party sites and press Submit request.

23andMe warns its users that uploading their data to other services could put genetic data privacy at risk. For example, bad actors could use someone else’s DNA data to create fake genetic profiles.

They could use these profiles to “match” with a relative and access personal identifying information and specific DNA variants—such as information about any disease risk variants you might carry, the spokesperson says, adding: “This is one reason why we don’t support uploading DNA to 23andMe at this time.”

Ancestory.com

Deleting your results

- Go to DNA settings

- Select the test you’d like to delete. You can only delete a test that you own or manage.

- Scroll to the bottom of your Settings page and click Delete next to Delete DNA Test Results And Revoke Consent to Processing.

- To permanently delete your AncestryDNA results, enter your password and click Delete Test Results and Revoke Consent. If you click this button

- Your AncestryDNA results are permanently deleted.

The recent political climate in New Zealand and recent scientific and technological advancements have reinforced concerns that we should be reconsidering they way we share our DNA and for privacy concerns of ourselves and wider intergenerational whānau, hapū and communities.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.