This thought-provoking commentary delves into the intersection of te ao Māori and Artificial Intelligence (AI) regulation. While many Māori have expressed a desire for AI regulation, this post raises the point that doing so too soon could have unintended consequences. It’s important to consider the implications of AI regulation from a te ao Māori perspective. Let’s continue to explore this topic and ensure that any decisions made are well-informed and culturally respectful*.

Until only recently, commentators in the AI and regulation space have been bias against Māori perspectives due to no Māori voices being considered, a matter that has now significantly changed.

Importantly, it must be noted that Artificial Intelligence is not a new technology and talk of regulating it has only become a popular topic in recent years, likely due to the public release of ChatGPT. AI begun its developments in the 1940’s to 1960 with several pathways of technological development occurring that has led to what we now consider AI. Many consider that it was not till 1956 that AI as a concept was initialised by Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw and Herbert Simon’s, Logic Theorist programme.

Two primary sets of research are analysed from a 2023 DataCom survey on business leaders use and the recent 2024 InternetNZ survey of New Zealand perceptions of online and AI. Also considered is research commissioned by The Law Foundation New Zealand and NetSafe research about online abuse that show Māori are more likely to be victims of online abuse in all of its forms.

In conclusion, an analysis of New Zealand legislation and legal frameworks, how they could impact AI regulation in New Zealand.

International Regulation of AI

Before starting the commentary about AI regulation in New Zealand, it is important to note that Artificial Intelligence (AI) regulation has become a growing topic of conversation internationally over the past few years.

Below are some regulations and guidelines below to consider:

- United Nations – Principles for the Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence in the United Nations System (2022)

- ISO AI Management System standard ISO/IEC 42001:2023

- The European Union have the Artificial Intelligence Act

- The United States of America, President Joe Biden issued an executive order to establish new standards to maximise the benefits of AI while safeguarding against its use.

- Brazil has a draft AI law https://policyreview.info/articles/news/road-regulation-artificial-intelligence-brazilian-experience/1737

- China has published a draft regulation for generative AI and is seeking public input on the new rules

- Israel in 2022, Israel’s Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology published a draft policy on AI regulation.

- In March, Italy briefly banned ChatGPT, citing concerns about how — and how much — user data was being collected by the chatbot.

- In February 2024, the Indian government announced is working on a draft regulatory framework for artificial intelligence (AI) and aims to unveil it by June-July this year.

New Zealand community perceptions

Recent research by InternetNZ in the report New Zealand’s Internet Insights 2023 shows there is a national interest in regulating AI. Based on the population statistics (Māori 17%) it appears Māori more likely than the rest of New Zealand society to want regulation.

New Zealanders who are extremely concerned / very concerned with AI related safety:

- Artificial Intelligence (AI’s) impact on society – 52% of all New Zealanders and 51% of Māori

- that young children can access inappropriate content – 73% of all New Zealanders and 74% of Māori

- the security of personal data – 69% of all New Zealanders and 68% of Māori

- Online crime 67% of all New Zealanders and 64% of Māori

- Identity theft 66% of all New Zealanders and 65% of Māori

- Information is misleading or wrong 65% of all New Zealanders and 60% of Māori

The report when read as a whole, shows there is an increasing awareness of the risks of technologies such as AI in communities and households. This does provide opportunities for the DigiTech sector to engage more with Māori and communities to seek solutions, correct false statements and to create new roles in AI.

New Zealand Business Leaders’ opinions of AI Regulation

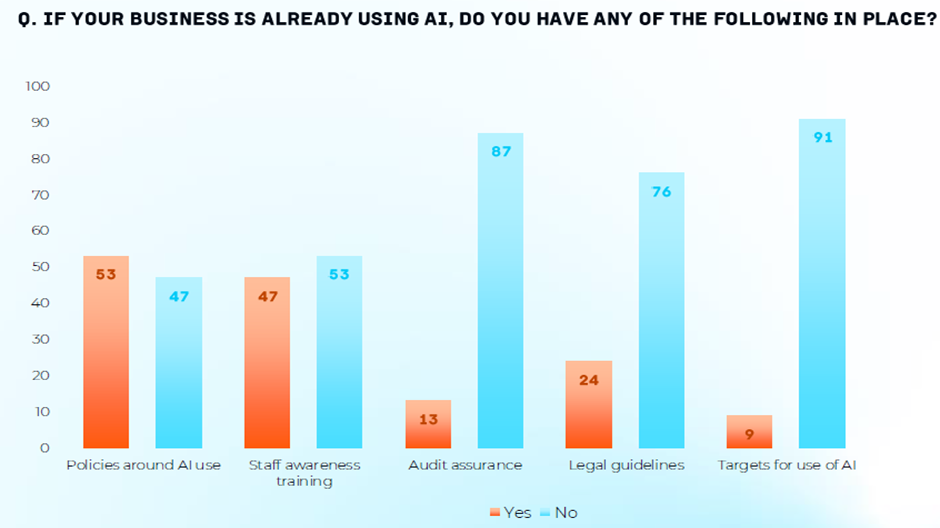

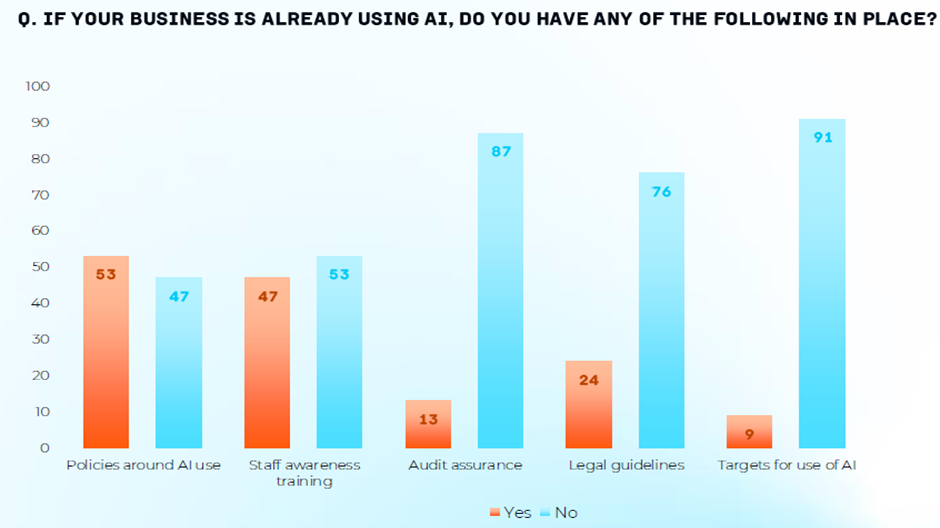

In 2023, DataCom released their report AI Attitudes in New Zealand, AI Attitudes Research, New Zealand. August 2023. The report surveyed 200 senior business leaders in New Zealand to understand rates of AI adoption, maturity of existing AI governance and security, appetite for AI-specific legislation and which sectors are seen to hold the greatest opportunities and risks for AI use (DataCom, 2023).

The need for businesses to have the right governance in place to balance the risks and rewards was noted in the report as was the need to forward-looking approaches from both industry and government to ensure New Zealand remains competitive.

The report has a powerful quote from a Managing Director that is worth to note in this commentary

“AI bias is something organisations need to be particularly mindful of. While AI can be used to support and drive diversity and inclusion initiatives, without the right checks and balances, it has the potential to do the opposite.”

50% of New Zealand InfoTech companies surveyed in the report were concerned about bias in AI algorithms that reflect human biases, 73% concerned about AI safety and 53% questioning the ethical use of AI in the wider society.

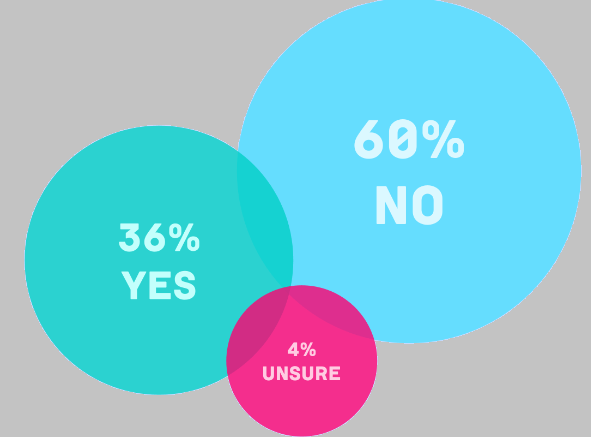

A staggering 82% of New Zealand InfoTech companies believe that the government should regulate AI.

Security

60% of businesses are concerned or do not feel educated about the security of personal data and Intelectual Property with AI. This is a real concern and as I will note later, the current legislation requires an update. Many artists around the world and in New Zealand share these concerns too.

Employee use of AI

69% of business leaders are supportive of their employees using AI such as ChatGPT (generative AI) to carry out their work tasks in the workplace. A minority of 11% (about 1 in 10) are opposed and 20%, or one in 5 were unsure.

This appears to show that New Zealand businesses are aware of bias and security issues with AI. The result should be that businesses with good governance practices will engage expert stakeholders to regulate against bias and to protect their organisations from litigation and security issues caused by the introduction of AI.

New Zealand Government Perspective of AI Regulation

Minister for Digitising Government, Science, Innovation and Technology, among other important portfolios, the Hon Judith Collins told the NZ Herald

“This Government is committed to getting New Zealand up to speed on AI. We have a cross-party AI caucus, which is due to meet soon. Its first step will be providing feedback on the AI framework we are developing to support responsible and trustworthy AI innovation in government, which the public should expect to hear more on in the coming months.”

“There will be no extra regulation at this stage.”

I agree with the Ministers statement. Any knee jerk reaction without proper considerations of all New Zealand society, business, industry collaborations, innovations, reviews of outdated legislation, and consultation could have negative impacts for parts of society from commercial, not for profits, minorities, and in particular Māori.

One recent example of this could be seen with the recently repealed Therapeutic Products Act 2023 which had significant impacts on Māori and was likened to the Tohunga Suppression Act 1908 that outlawed many Māori customs including medicines, by many Māori natural medicine practitioners.

New Zealand legislation and Frameworks

There is a common response that AI does not need to be regulated as we have current legislation and frameworks to protect New Zealanders. The following are commonly used as examples, but below I will explain how a Māori perspective is not considered.

Privacy Act 1993 does not recognise a Te Ao Māori perspective with Privacy and largely contradicts Māori Data Sovereignty. It is solely focused on individual privacy rights with no considerations for collective sharing with whānau and other social groups as identified in the High Court case Te Pou Matakana Limited v Attorney-General (No 1) [2021] NZHC 3319 (WOCA 2). Nor does it consider the Supreme Cour case Peter Hugh McGregor Ellis v R [2022] NZSC 115, 07 October 2022 where Tikanga Māori (traditional customary lore) is New Zealand’s first common law.

There is the section in the Act where the Commissioner must consider cultural values. Privacy Act 2020 Section 21 (c) states that “Commissioner to have regard to certain matters take account of cultural perspectives on privacy. At this stage it is too ambiguous and Māori will need to continue to seek clarification on this section with different circumstances.

The guidelines of the Media Council of New Zealand. These guidelines have been analysed by a number of Māori academics and have consistently found bias to Māori in the media including: How news items represent Māori , Racism and silencing in the media in Aotearoa New Zealand , Our Truth, Tā Mātou Pono: The Press’ bias has failed Māori , Decolonising the news: 4 fundamental questions media can ask themselves when covering stories about Māori. The guidelines would benefit greatly with a set of Māori perspectives.

Harmful Digital Communication Act 2015. It is very difficult for any victims to get justice. Māori are more vulnerable than many others and are increasingly becoming a victim group whose cultural values are ignored.

Social Media platform guidelines are just that, guidelines. No Social Media platform guidelines that were sourced for this article consider Te Tiriti o Waitangi or a Te Ao Māori perspective, let alone were they enforceable. My yet to be published research has proved these guidelines are ignored in New Zealand with racist and pornographic content in social media such as FaceBook.

Copyright Act 1994 has never considered Māori intellectual property rights and is already overdue for a review due to technologies. No country in the world has suitably addressed Indigenous collective property rights.

Further to this, the Copyright Act has been waiting for the findings from the WAI 262 claim which underpins a significant amount of New Zealand’s Intellectual Property laws including the Patents Act 2013 and Trade Marks Act 2002, recommendations and how to implement them. Of note, we have already seen overseas that AI generated art and the multiple legal issues that arises from this.

There are a number of laws in New Zealand that already require to be updated to adjust to the digital revolution before any new regulation is introduced. While the updates are being considered by Parliament, it would be an ideal time to also consider Māori and other minorities to guard against bias and discrimination.

Other considerations

In my published chapter in Goffi E. R., Momcilovic A., et al. (Eds). Can an AI be sentient? Multiple perspectives on sentience and on the potential ethical implications of the rise of sentient AI. Notes n° 2, (2022). Global AI Ethics Institute., available as a blog post.

Using the following New Zealand personhood cases, I discuss the implications to AI of personhood.

- Te Urewera Act 2014

- Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Bill 2017

- Record of Understanding Mount Taranaki 2017

This also gives Māori a unique opportunity to consider contributing to the Digital Identity Services Trust Framework Act 2023 (Disclaimer I am a member of the Māori Advisory committee). At least it presents an opportunity for Te Ao Māori to consider these issues and how they could impact Te Ao Māori.

The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007, that New Zealand agreed to in 2010 is also an important legal instrument that recognises Indigenous Peoples rights to technologies such as AI.

The following Waitangi Tribunal findings are also important to consider when discussing AI regulation and a Te Ao Māori perspective:

- The WAI 262 claim is commonly known as the “flora and fauna” claim. WAI 262 addressed the ownership and use of Māori knowledge, cultural expressions, indigenous species of flora and fauna, all known as taonga (treasures), and inventions and products derived from indigenous flora and fauna and/or utilising Māori knowledge.

- The WAI 2522 claim found that Māori Data is a Taonga and subject to Māori Governance/Māori Data Sovereignty.

Based upon the Waitangi Tribunal have emerged two sets of Māori ethical principles that could also be considered and implemented:

- 6 Te Tiriti Based Artificial Intelligence Ethical Principles

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi Principles for Robotics

Deepfakes are emerging as a new online threat, in particular with elections and pornography. Everyone in human society is likely to be impacted by this technology. Māori face the same possibility as any other societal group to manipulation and hurt by this technology.

Research commissioned by The Law Foundation New Zealand “Perception Inception: Preparing for deepfakes and the synthetic media of tomorrow. ”

The report makes a number of recommendations, including closer ongoing investigation by collaboration between legal and technological subject matter experts. I consider Māori cultural practitioners should be considered subject matter experts and that considered of the section above on New Zealand Legislation would be beneficial.

Among the 27 recommendations are:

“We recommend caution in developing any substantial new law without first understanding the complex interaction of existing legal regimes. Before acting, it is essential to continue to develop an understanding of how these regimes apply to factual scenarios as they arise. Where new law is necessary, it is likely to take the form of nuanced amendment to existing regulation.

For now, existing legislation should be given the opportunity to deal with harms from synthetic media technologies as they arise.” (pg. 18)

AND

“Any new legislation must take the position that synthetic media technologies and artefacts touch upon individual rights of privacy and freedom of expression, deserving careful attention from policymakers and broad public consultation. There are benefits, risks, and trade-offs to be discussed in deciding whether to allocate responsibility for restricting synthetic media technologies to the State or to private actors. Human rights, the rule of law, natural justice, transparency and accountability are essential ingredients in whatever approach is adopted.” (pg. 18)

Facial Recognition technologies from a Te Ao Māori perspective are discussed here.

New Zealand Algorithm Charter

As Chris Keal states in his NZ Herald article, Professor Juliet Gerrard said in July last year

“The only AI-specific policy is the Algorithm Charter, which most Government agencies have signed up to.”

The Herald article omitted criticisms of the Charter. Dr Andrew Chen of the Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures raises a number of issues including “The Charter doesn’t really engage with Māori, including in terms of Māori data sovereignty.” Dr Chen wrote more extensively on the topic in More Zeros and Ones which also cover my own concerns that the charter further significantly failed Māori by being overly tokenistic.

Taylor Fry reviewed that Algorithm Charter for Aotearoa New Zealand after its first year in December 2021 . Overall, the new review scores the charter’s first year: ‘OK, could do better’. But made a number of concerning findings, but largely did not consider Te Tirti in its findings, only as a reference.

RadioNZ noted Plus, compliance was very light-handed. “Some greater enforcement might be necessary to keep social licence.” This appears at odds with OECD principles on artificial intelligence that say how systems work should be disclosed so people can challenge them.

Among the Algorithm Charter signatories are government departments who have and continue to be accused of bias and racism against Māori including: Ministry of Health who the Waitangi Tribunal in the Hauora: Report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry (WAI 2575) was found to systematically discriminated against Māori.

Noting government algorithms impact the individual as well as collectives, the Algorithm Charter could benefit from a wider Te Ao Māori consultation and multiple Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreements including from the AI industry groups below and other Māori, hapū, iwi and community groups. This would ensure that wide and reflective Māori society perspectives are captured. In partnerships, the Charter could be an effective way of working with expert stakeholders, industry and government and would avoid the need to consider regulation.

Māori representation with AI

Over the past 14 months, the lack of Māori representation in AI (technical and ethical) has significantly improved with reputable AI organisations ensuring there are open and transparent invitations to Māori to express and to consult with regarding Māori and Iwi issues. Thus giving a wide and representative Māori voices an opportunity to contribute myriad of skills to AI policies and guidance.

The primary New Zealand organisations include: the AI Forum who is an industry member based organisation with a Kāhui Māori that are actively seeking other Māori voices and ensure that Te Tiriti and Te Ao Māori is heard across all of their work, Artificial Intelligence Research Association is an organisation of academic researchers with a clause in their constitution recognising their Commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi and have co governors and a dedicated group of Māori academic researchers, The Office of the Privacy Commissioner are engaging with Māori and Iwi over various privacy issues such as Biometrics and the Privacy Foundation New Zealand a group of privacy experts who actively seek and work with Māori and have a public commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Conclusion

Currently New Zealand has no regulation of AI with the government, researchers and a strong Te Ao Māori perspectives are that regulation of AI is not currently needed in New Zealand. What is required is for the Ai industry, legal experts and expert stakeholders such as Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations to work together to identify existing laws and amend them and to include Te Tiriti based principles to avoid bias to Māori. It is also an opportunity to consider national data sovereignty and Māori Data sovereignty principles.

There is an opportunity for more Māori and New Zealand perceptions of AI to be undertaken to fully inform the decision makers of AI regulation.

Any sudden regulation of AI in New Zealand would likely be premature and cause a number of unintended consequences to Māori and other areas of New Zealand society. If at some future date regulation is considered, then it must be in a consultative and fact-based research justifying why regulation of AI is required and who it will impact.

* Rewritten by LinkedIn AI. Original text was “This commentary explores and considers a te ao Māori perspective (Indigenous Peoples of New Zealand) with Artificial Intelligence (AI) regulation and why, despite many Māori suggesting they want AI regulated, that by doing so could be premature and could have unintended consequences.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.