This article was originally commissioned by Ngā Toki Whakarururanga for a general audience. For a Te Ao Māori perspective, refer to my 2020 article Māori Cultural considerations with Facial Recognition Technology in New Zealand.

Since the news attention in February 2024 that Foodstuffs North Island Limited‘s New World and PAK’nSAVE is trailing Facial Recognition Technology in supermarkets (Radio Waatea, Te Ao Māori News, RNZ) in the following towns: Brookfield Tauranga, Hillcrest Rotorua, Whitiora Hamilton, Napier South, New Plymouth Central, Silverdale and Tamatea, Napier.

This article has been updated and made more applicable to the current situation.

Introduction

We use our image of our face as a modern-day password for many things including mobile banking, unlocking our phones, X (formerly Twitter), Firefox Klar and an ever-increasing number of other online services. For some beneficiaries of Ministry of Social Development (MSD) they controversially use Facial Recognition to self identify themselves.

For law enforcement agencies, Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) systems are used to decide many factors including who becomes a suspect in a police investigation. Now many consumers in New Zealand who visits New World or PAK’nSAVE supermarkets will likely be profiled with Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) in an effort to make shopping safer for customers and staff. This despite the wide and increasingly growing research of the bias and ineffectiveness of FRT has against non white males.

Citizen’s rights and social justice groups, alongside the research community, have identified undesirable societal consequences arising from the uncritical use of FRT algorithms, including false arrest and excessive government surveillance. Amnesty International have called for a ban on FRT.

Within the United States, the consequences have disproportionately affected people of colour, both because algorithms have typically been less accurate when applied to nonwhite people, and because—like any new forensic technology—FRT systems are being incorporated into systems and institutions with their own histories of disparities. https://mit-serc.pubpub.org/pub/bias-in-machine/release/1

Facial Recognition Technologies (FRT) also pose risks to personal security such as governments purchasing sensitive data https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/when-the-government-buys-sensitive-personal-data, face images sold to data brokers and advertisers, our images and data stolen and used for criminal activities to hack our personal bank accounts, phones etc.

A more widespread risk is that of deep fakes. Deepfakes often transform existing source content where one person is swapped for another https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/deepfake . Innocent people have had their images taken from the web and used in deep fakes in pornography, conspiracy theory videos, hoaxes, and adverts.

Facial recognition systems are the digital equivalent of the old colonial practice of collecting Māori heads or mokomokai. Our Faces and images including our moko are being taken without permission by the government and used in ways we are still not certain of. Though we are learning a lot from Official Information Requests by the media.

From a New Zealand perspective, Māori, Pasifika and our international citizens of colour, more likely women (as the statistically more likely demographic to grocery shop for the household) will likely face discrimination, false accusations, trauma and other negative experiences due to Facial Recognition Technologies. There is no legislation to manage FRT and CCTV, but the Privacy Commission have guidelines and have undertaken consultation in this area.

Internationally

Within the United States, People of Colour suffer the consequences of mistaken identity and bias disproportionately more, because algorithms typically have been less accurate when applied to nonwhite people. As with any new forensic technology, FRT systems are being incorporated into systems and institutions with their own histories of disparities.

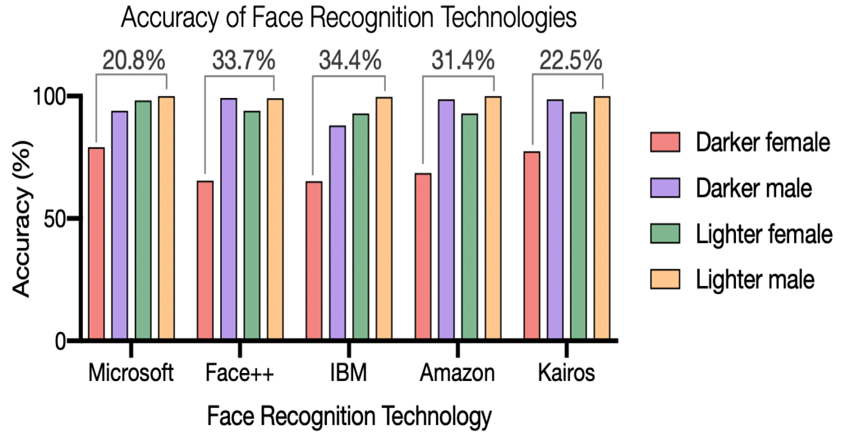

In 2018 and 2019, detailed studies by researchers at MIT, Microsoft Research and at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) identified persistent inaccuracies in algorithms that were designed to detect and/or identify faces when applied to people of colour https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Yet, facial recognition algorithms boast high classification accuracy (over 90%) when used on white people.

Fig 1: The Gender Shades project These algorithms consistently demonstrated the poorest accuracy for darker-skinned females and the highest for lighter-skinned males.

New Zealand

In a New Zealand context, FRT threatens to exacerbate the well documented bias and discrimination against People of Colour and Indigenous Peoples such as Māori who are already subjected to well documented racism and bias with government agencies including by the New Zealand Police.

Facial Recognition Technologies (FRT) are used by many councils, government departments including Corrections and Immigration, many workplaces including retail, and in private residential homes for security. In 2017, The Department of Internal Affairs ran tests on 400,000 people’s passport photos to decide which FTY system to buy. Alarmingly, the use of FRT continues to grow with some experts calling for moratoriums.

The Police halted FRT after an expert report: “Facial Recognition Technology: Considerations For Use In Policing” found a general lack of awareness among the Police of their obligations under the Privacy Act 2020, and that accuracy and bias were the key concerns with the use of FRTs, further collaborating international research. The report warned it would impact Māori the most if they used FRT .

One reason why Māori could be impacted the most is that the Police have large databases of images of suspects and was found to be taking photos of Māori in breach of the law and that those acts were likely an issue of bias.

“Moreover, in 2020, the New Zealand police trialled a system called Clearview AI and it was a particularly, spectacularly unsuccessful trial. Clearview AI screens scraped three billion images of people from Facebook, TikTok and other social media platforms with the NZ Police finding only one match” .

RNZ revealed via an Official Information Act Request that the Police use BriefCam which has AI-enabled video surveillance and capability for targeted and mass surveillance activities to analyse CCTV footage for faces and vehicles.

Any digital images of Māori faces are likely to become the legal property of others as is the case with many social media services now. Due to this and the lack of regulation, we have already seen the appropriation of Māori faces and moko on shower curtains, emoji’s, cigarettes, and alcohol labels to name a few. As facial technology increases, the risks for further abuse and discrimination against Māori is likely.

Further Risks

Facial Recognition algorithms are designed to return a list of likely candidates based on comparing a photo to the database photos using biometric measurements. The next recommended step is that a human investigator confirms that there is a good match from the FRT, and then seeks additional evidence, such as eyewitness testimony or forensic evidence from a crime scene etc, to justify arresting a particular subject.

Foodstuffs have stated they have specifically trained staff to verify images that are a 90% or higher match. This in itself can be another issue. Increasingly, there are reports that the human investigator check does not occur, as humans appear to trust the output of an algorithm thinking it must be “objective” more than their own judgment. This has resulted in an ever increasing number of falsely accused innocent People of Colour being arrested “Wrongfully Accused by an Algorithm”, “Another Arrest, and Jail Time”; “Wrongful Arrest Exposes Racial Bias.

In Aotearoa New Zeeland we have unique cultural issues that must be considered with FRT including how will the human interaction staff be skilled with sensitively identifying differences of moko between one person and another? We will see a new range of identity theft crimes begin. The days of moko wearers having their moko stolen for use in art will be considered an old type of theft. Already the technologies exist to 3D print a replica face mask of a human being, extract a moko from an image on the Internet and print it out and apply it to a face, or any part of the body. Criminals will start to imitate others to get around Facial Recognition Technologies and we will likely start to see criminals and people concerned about their privacy covering up their faces in ways that will make it harder to identify them.

The fact that associates of identified shop lifters can also be trespassed from the supermarket; there seems very little consideration of Māori societal structures and the fact that many inter generational family members are likely to live together and to support each other at such events as grocery shopping and that many communities and families have criminals and gang members. Will these communities and family units be discriminated against simply for having Māori family values?

Māori Traditional knowledge warns of the issues of Facial Recognition Technologies. Among many traditional stories is the story of Māui and one of his wives Rona, who was a beautiful woman, but Māui stole her face.

There need to be questions about how the face and moko are stored, analysed, and distributed amongst international networks and what privacy and protection mechanisms are in place. With the current technologies and storage associated with Facial Recognition Technologies, there will be breaches of Intelectual Property Rights issues, Te Tiriti breaches and tikanga offences for Māori, especially those who wear a moko and of Māori Data Sovereignty principles and Māori Data governance.

With FRT technologies, images of our faces can be stored in overseas jurisdictions including the following laws: The Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (CLOUD Act) (H.R. 4943) The USA PATRIOT Act (commonly known as the Patriot Act), The Stored Communications Act, US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA 702), The Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (International Production Orders) Bill 2021 and the Overseas Production Orders Act 2019 (COPOA).

Some of our images could be sold by collectors (CCTV and other vendors) to, and or collected by government agencies who will use the images with no consideration of cultural values. These images are being stored overseas and subject to other countries laws.

Facial Recognition Advertising

Facial recognition advertising is the use of sensors that recognise a customer’s face, or biometrics. Adverts can then instantaneously be changed to suit the customers shopping habits based on data in real time. The goal is to create dynamic ads that adjust to appeal to a person’s interests the moment they notice the ad.

In the USA, Walgreens has installed in their freezers front-facing sensors used to anonymously track shoppers interacting with the platform, while internally facing cameras track product inventory https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/12/business/walgreens-freezer-screens/index.html.

Facial recognition advertising could lead to bias and discriminatory adverts against Māori, based on data. An example; alcohol consumption is highest in men (83%), those identifying as European/Other (85%) or Māori (80%), and people living in the least deprived neighbourhoods (86%). This would likely mean the facial recognition advert algorithm would target alcohol adverts to Māori men and people living in the least deprived neighbourhoods who are typically Māori and Pasifika.

Other risks to Māori are intergenerational households including the risk of a Māori mother shopping for her children and other members of the household whānau. The grocery items could be varied, but those products will be added to her profile. If there are sexual health products for a teenager and alcohol for adult, the profile could be degrading and result in advertising that is not appropriate of wanted.

Looking Forward with Solutions

While New Zealand is still at the very early stages of Facial Recognition as a crime prevention tool being introduced, there are multiple options for Māori to combat the bias of Facial Recognition Technologies including participating in consultations with the Privacy Commission and government.

For technical people, there are several national technology organisations with Working Groups of experts addressing these issues and there is the Digital Identity Services Trust Framework legislation that has a dedicated expert Māori advisory group raising and consulting with Māori as individuals and collectives.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.