Also see Māori Data is a Taonga Chapter

Also of interest and diverse views, an interview in English with myself, Tau Henare and Ngapera Riley discussing Māori Data as a Taonga https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57nFcXAycFg

2018 version (original)

This paper has been written to fill a void of information about data being a taonga and why there are various views by Māori.

Government views of Data as a taonga

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

Indigenous thinking of the digital ecosystem

Introduction

For the purposes of this paper, the definition of Māori data is:

- Data that is held by Māori, made by Māori or contains any Māori content or association. This includes Information such as archives, records etc.

This paper has been written to fill a void of information about data being a taonga and why there are various views by Māori.

Individuals and organisations are discussing Data being a taonga, yet there is confusion about what is a taonga and how data is a taonga. Some articles say only some Data is a Taonga. I do not believe there are any articles that consider a customary Māori view of data. Many published articles and references are academic texts that are hard to read yet do not state any customary views.

Many of the sections of this paper are brief, as each section constitutes years of knowledge and a Māori worldview that can never be adequately compressed into such a paper. However, the information in this paper does cover some basics, albeit at a high level. This should create a platform from which to launch further research, debate and investigation.

Governments and commercial entities consider data to be important. Internationally data has become a new commodity that is sold and traded on markets. In New Zealand data is used for social and economic development among other things. If the New Zealand government didn’t place a high value on the data it holds, it would be obliged to not retain or create the data.

Because of the western perspective that data is anonymous, the New Zealand government and other governments have treated data about its people and land as terra nullius. By digitizing Māori data and information without permission or consultation they have breached traditional Māori customary rights and beliefs. It is too late to prevent the digitization and dissemination of taonga in the web and in digital repositories, but it is not too late to be considerate of customary rights/beliefs and to lessen any future impacts.

If we consider the early colonisers to New Zealand who normalized the practice of collecting human body parts such as heads. Society and government did not see anything wrong with this barbaric practice. It is no longer socially acceptable. Only recently has repatriation of these human remains began. With the same knowledge learnt by history, we now must contemplate how many years will go by till we repatriate our data?

Tipuna Māori gave ethnographers tapu information for paper medium created by metal plates. The distribution was severely restricted to those who could purchase a book. Informants had no idea of the Internet and information flow and speed of that flow. Data today faces a similar fate. Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence are future risks that will affect Māori Data in ways that no one has yet realized the potential impacts to Māori.

What is a taonga

Before discussing why data is a taonga, we need to first look at recognised definitions of the term taonga.

- The term taonga defies any exhaustive definition, and in summing up the findings of a number of Tribunal reports the Tribunal stated in the Petroleum Report of 2003 (The Petroleum Report (WAI 796, 2003) at [5.3].)

Though the term has a number of other more mundane meanings, successive carefully reasoned reports of the Tribunal over many years now have come to treat ‘taonga’, as used in the Treaty, as a tangible or intangible item or matter of special cultural significance. - The courts have also acknowledged that the status of taonga applies to the tangible and intangible, accepting both language and familial organisation as examples of intangible taonga. See in respect of language see New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General HC Wellington CP942/88, 3 May 1991; New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 (CA) and [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC); in respect of familial organisation see Barton-Prescott v Director-General of Social Welfare [1997] 3 NZLR 179 at 184.

- Lord Woolf of the Privy Council followed the approach of the Court of Appeal as well as the Tribunal in the final Broadcasting Assets decision stating:

The Maori language (Te Reo Maori) is in a state of serious decline. It is an official language of New Zealand, recognised as such by the Maori Language Act 1987. It is “a highly prized property or treasure (taonga) of Maori” (Cooke P [1992] 2 NZLR 576, at p 578 in the Court of Appeal) and it is also part of the national cultural heritage of New Zealand. New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney General [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC) at 513. - New Zealand courts have also discussed the notion that taonga may not necessarily be held by Māori, made by Māori or hold any Māori content or association. See Jacinta Ruru’s discussion of the cases of Page v Page (2002) 21 FRNZ 275 and Perry v West HC Auckland CIV-2002-404-002114, 15 December 2003 in Jacinta Ruru “Taonga and Family Chattels” [2004] NZLJ 297.

The definitions of a taonga used by the Waitangi Tribunal mean that any taonga is protected under the guarantees in article 2 of the Māori text of the Treaty of Waitangi which states:

The Queen of England agrees to protect the chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures. But on the other hand the Chiefs of the Confederation and all the Chiefs will sell land to the Queen at a price agreed to by the person owning it and by the person buying it (the latter being) appointed by the Queen as her purchase agent.

It is important to note here that some claims to the Waitangi tribunal regarding taonga have been unsuccessful and there is not yet a claim for data as a taonga.

Mana Raraunga the Māori Data Sovereignty Network state that Māori Data should be subject to Māori governance, therefore Article 1 of the Treaty (Hudson, 2018).

The Government Chief Data Steward’s Data Strategy and Roadmap For New Zealand has a section called “Commitment to the Crown-Māori Treaty Partnership”.[1] While there is misunderstanding about the tikanga involved, it does form a good basis for a foundation with which to work upon.

New Zealand recognises the importance and value of the Treaty of Waitangi that establishes Māori as Partners with the Crown. There are new opportunities for the Crown to engage with Māori on the full breadth of issues in the current environment to ensure the Crown is meeting its Treaty obligations and supporting Māori to activate their full potential in a new world of possibility. Two Māori values in particular will support a trusted data system: manaakitanga (data users show mutual respect) and Kaitiakitanga (all New Zealanders become the guardians of our taonga by making sure that all data uses are managed in a highly trusted, inclusive, and protected way).

Māori world view

All Māori are born with whakapapa but not all Māori are Māori practitioners. There is no one Māori world view, in as much as there is no one New Zealander world view. Māori are diverse as a people.

Māori societal structure is made up of descendants from the original waka that arrived in New Zealand. Then whānau who make up a larger hapū who are associated to the larger Iwi. Each whānau, hapū and Iwi have their own lore’s and values, though not so dissimilar as to be totally foreign to each other. StatsNZ recognise 137 Iwi. There is no records of how many hapū exist. Ngā Puhi according to Tūhono have about 278 hapū[2]. Ngāi Tahu have 136 hāpu[3]

Mead (Mead, 2016) asserts that in 1979 it was obvious that few people really understood tikanga, and this included our own people. Timoti Karetu also laments the loss of kawa on the marae in 1978 when he stated “it is more important to take a stand now and rescue what we can from those few kaumatua still living before the take their knowledge with them to the grave (King, 1978).

The loss of traditional knowledge, tikanga and kawa is likely due to the facts that Māori culture has been integrated into European culture for over 400 years by colonisation, intermarriage, introduced and forced religion, urbanisation, legislation and educationalists encouraging the move away from Māori culture and government imposed assimilation.

There has also been 400 years of heavy missionary influence introducing new religions that taught that Māori religious beliefs were bad. Many Māori adapted to these new religions, leaving behind their traditional knowledge systems and beliefs. Māori had many forced intermarriages into other different cultures through the colonization process. There were also customary intermarriages between hapū and Iwi.

A common argument against tikanga and customary rights are that they are no longer relevant. The same is often said of the Holy Bible and religion. Others believe that the Treaty of Waitangi is also obsolete in this age (Archie, 1995). Tikanga and the Treaty of Waitangi are both relevant and are unique building blocks for modern day New Zealand society. For many Māori, traditional tikanga is still applicable and highly relevant, though for some it is just instinct that cannot be described.

It is not uncommon for governance appointments to select a Māori simply because they are Māori, with no regard to if they are a practitioner or not. This has long been an issue in all aspects of Māori society. When appointments disagree with other Māori, then it is considered in fighting or tribal. No consideration about the diversity of Māori society.

Another modern day issue of Māori consultation is when the consultants have alternative interests. They will challenge traditional knowledge views and social peer pressure to say what the organisation want to hear, thus securing a contract and future relationships.

Māori academics have institutional boundaries they must work within. Western sciences and knowledge institutions do not recognise traditional knowledge, therefore how do Māori academics publish material about tikanga and mātauranga Māori?

Cooper (2012) states that Māori knowledge has been cast by Western science into an epistemic wilderness, and Māori are regarded as producers of culture rather than knowledge.

The position of Kaupapa Māori is paradoxical. It must stand aloof from the concerns of science and centre Māori epistemologies as a starting point for research. At the same time it must critically engage Western knowledge and production practices as part of its decolonizing and transformational strategy (Cooper, 2012)

For an organisation to get a balanced Māori world view, an advisory group needs to be a mixture of Māori. Not geographically diverse but knowledge based. There needs to be traditional Māori knowledge mixed with academia and end users who are all Māori practitioners.

Traditional Knowledge

Māori cosmology stories include a story about data and why it is a taonga. This is a basis for data today being a taonga. This story varies slightly depending on the Iwi so this will summarize the traditional knowledge.

In the heavens were three baskets of knowledge that contained all the knowledge for human beings. Tane one of the many sons of Rangi and Papa was sent to bring the baskets back to earth. Tane was attacked by his evil brother Whiro who wanted the knowledge for himself. But Tane and goodness fought off the attacks.

These baskets by todays terms would be data storage pertaining to all things in life. This traditional knowledge gives data a whakapapa. Anything with whakapapa is a taonga.

Whakapapa in its simplest sense is genealogy, in a wider sense whakapapa attempts to impose a relationship between an iwi and the natural world. Moreover, whakapapa is a metaphysical framework constructed to place oneself within the world (Tau, 2003). Whakapapa is one of the most prized forms of knowledge and great efforts are made to preserve it, P: 174 (Barlow, 1991).

Traditional knowledge also tells us that every natural object and living thing has a spiritual aspect. If we sit down, our mauri sits down with us and some mauri can be left behind if not considered. Likewise, having our photograph taken contains the mauri of the persona. Hence, photos are the dead are tapu.

Māori Data has Mauri, Whakapapa. Data is no different. If it is about a person, their mauri is associated with the data. Therefore, any data and recorded information is a taonga because of these Māori beliefs.

Mauri: In te ao Māori, information is tapu and contains the tapu of the person it is about. Once you learn new knowledge it becomes a part of your mauri. Hence knowledge was not always provided and could not be provided. Because of this, knowledge has been taken by academics and governments without permission.

Another traditional Māori belief is that if information is made copied or made electronic, then the person involved can become sick, or cursed. This is further complicated when the data is mixed with data about both the living and the dead.

John Rangihau explains the process of gathering and learning new information:

I talk about mauri and some people talk about tapu. Perhaps the words are interchangeable. If you apply this life force to all things – inanimate and animate – and to concepts, and give each concept a life of its own, you can see how difficult it appears for older people to be willing and available to give out information. They believe it s a part of them, part of their own life force, and whey they depart they are able to pass this whole thing through and give it a continuing character. Just as they are proud of being able to trace their genealogy backwards, in the same way they can continue to send the mauri of certain things forward (King, 1978).

Some Māori will say data has no Mauri as data is anonymized. If you consider a Māori world view and consider the statement from John Rangihau above. Then, because data originated from a person, people or other living thing in the Māori world, the data does have a mauri. Therefore, in a Māori lens, it is only anonymized is a western lens unless a tapu removal ceremony was correctly performed on the data. This would raise other issues as to who has the authority to do it and how do you perform such rites in a digital environment. Therefore, a system which has Māori data must also become tapu as it contains the mauri of the people and things contained in the data and information.

Because data has a mauri, whakapapa of the data should be recorded, not because is a system requirement or law, but because it is Māori. The responsibility is on the data collector to record where the data came from, what the data is about, Iwi and hapū connections, and kaupapa Māori categories for metadata and to treat the data with respect.

Digital Colonisation

Definition sourced from (Taiuru, 2015a)

- A dominant culture enforcing its power and influence onto a minority culture to digitize knowledge that is traditionally reserved for different levels of a hierarchical closed society, or information that was published with the sole intent of remaining in the one format such as radio or print.

- A blatant disregard for the ownership of the data and the digitized format, nor the dissemination.

- Digital data that becomes the topic of data sovereignty.

- Digital and Knowledge workers who consult Māori to digitise their content and then digitise the content, but who fail to explain the power of technology and the risks including losing all Intellectual Property Rights.

- Conglomerates and government who use their influence to digitize data without consultation.

- A colonial view and approach to new Internet technologies such as New General Top Level Domain Names (GTLD) and Country Code Domain Names (CCTLD).

- Digital access where an ethnic minority are the majority digital divide stakeholders; often while their knowledge and resources are being digitised.

- Commercialisation of minority cultures CC TLD’s.

- Commercial entities paying translators to create new terminology for software and systems, then claiming ownership of the new terminology.

- Manipulation of search engine results to hide or change Traditional Knowledge.

Government views of Data as a taonga

The Government Chief Data Steward’s Data Strategy and Roadmap For New Zealand makes statements that allude the importance of data and refers to Data being a taonga[4]: The roadmap states:

- Two Māori values in particular will support a trusted data system: manaakitanga (data users show mutual respect) and Kaitiakitanga (all New Zealanders become the guardians of our taonga by making sure that all data uses are managed in a highly trusted, inclusive, and protected way).

Other statements that reinforce that Data is a taonga recognized by government:

- We envisage a future where data is regarded as an essential part of New Zealand’s infrastructure…

- Our ambition is to unlock the value of data for the benefit of New Zealanders.

- The value of data lies in its use

- The availability of new data sets and sophisticated technologies has enabled new and exciting data uses that continue to transform how individuals see, act and engage with the world.

- Data fuels the digital economy, modernising our way of life and enabling innovation across industries and sectors.

- We are increasingly seeing new uses of data that will impact our world in profound ways in the near future.

- The uptake in new technologies such as cognitive computing and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are enabling new and innovative data uses that continue to transform how individuals see, act and engage with the world.

Choosing an Iwi role models

New Zealand government consultations have for many years been accused of being selective with Māori they consult. It could be argued that this is again occurring with justifications to host Māori data overseas. The over reliance on ‘selected’ Maori experts and advisers with regard to GM is allowing tikanga Maori to be redefined and reinterpreted to provide an acceptable analysis of this technology within the Maori cultural paradigm;Research teams interested in promoting their research, universities conducting this research and government agencies promoting this research seek these ‘selected’ Maori experts to legitimise their work (Hutchings, 2005).

It is becoming common for government and commercial entities to justify offshore cloud based hosting of Māori data using The Office of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (oTRNT) often referred to as Ngāi Tahu. Despite the fact that the office is a western corporate structure that has ignored tikanga Māori. Eruera Tarena (Prendergast-Tarena, 2015) mentions the structure is “Adopting Western technical tools has unintentionally resulted in also adopting Western cultural values and practices into the organisation”. Tarena further sates: There is widespread belief that mimicking Western organisational structures and their associated cultural beliefs risks further assimilation (Prendergast-Tarena, 2015).

Ngāi Tahu is the fourth largest Māori iwi (tribe) and has the largest tribal territory covering 80% of New Zealand’s South Island. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu was established in 1996, by an independent act of parliament giving the tribe a long sought after legal identity.

Traditionally Ngāi Tahu were made up of about 137 hapū. Today there are 5 primary hapū. The five primary hapū have no governance or legal structure. There are 18 Papatipu Rūnanga who form the governance table for The Office of Te Runanga o Ngai Tahu.

Iwi member registrations are about 56,000 registrations. The office estimate that only about 10% of registered members participate or are active within a rūnanga. One could extrapolate that only about 5800 Ngai Tahu members are active with any rūnanga.

The operations of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu are managed by a CEO and its management team. One of Te Rūnanga’s earliest policy decisions was to employ the ‘best person for the job’, which gave the iwi credibility in the wider society, but resulted in large numbers of non-Māori staff, executives, and governors, especially in the investment arm (Prendergast-Tarena, 2015). This makes Ngāi Tahu different than many other Iwi organisations who predominantly employ their own Iwi members.

Ngāi Tahu have never had a Ngāi Tahu or Māori IT Manager or CIO and there are no kaupapa Māori policies relating to data, nor has there ever been one. Ngāi Tahu simply use standard corporate systems and IT environments.

Further to the western corporate structure. Historically, Ngāi Tahu were heavily colonised and had wide spread intermarriages diluting traditional Ngāi Tahu mātauranga and tikanga. Both important aspects when speaking about Māori Data Sovereignty. There are small pockets of whanau with the traditional knowledge.

A Ngāi Tahu Upoko and Canterbury University Scholar Professor Te Maire Tau has described that lack of cultural knowledge within the Ngai Tahu Iwi. His statement reinforces (Mead, 2016) observation that in 1979 it was obvious that few people really understood tikanga, and this included our own people:

Ngāi Tahu have been so colonised and have lost their identity, that it would be difficult to garnish any traditional knowledge. By 1996, Ngāi Tahu had no native speakers. In 1992, Pani Manawatu, the Upoko of the Ngāi Tu Ahuriri Runanga and last native speaker of the language, died. His death had been preceded by that of his cousin, Rima Te Aotukia Bell (nêe Pitama), who was learned in tribal traditions. In 1996, Jane Manahi, a spiritual elder and leader from Tuahiwi, also passed beyond the shaded veil. These deaths and the 1996 Te Runanga o Ngāi Tahu Act saw the end of Ngāi Tahu old and the evolution of a Ngāi Tahu new. Just as the Gauls and Germanic groups de-colonized themselves and rebuilt their world, so too have Ngāi Tahu (Tau, 2001): Pg148

To use Ngāi Tahu as the justification for offshore data storage is perpetuating a long established colonial tool to garnish predetermined results to justify their actions. (Williams & New Zealand. Waitangi, 2001) provides several examples of ethnographers who were products of their own culture, white, male and Christian who were bias with their research. Elsdon Best only spoke to chiefs about agriculture, yet only women in the area were the experts in medicinal values of plants. It is also unlikely that the chiefs were experts in agriculture. In 1790’s the British authorities wanted to establish a flax industry on Norfolk Island so took two Māori men. Flax work was done by women in the iwi that the men came from. Hence, they were of no use.

The case of Ngāi Tahu justifies the need for a definition of an Iwi organisation that is representative of Māori and Iwi.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

The following sections should be considered for Māori data and stored information:

Sections; 1,2,3,7,8,9,11,12,15,16,21, 25, 27, 31, 39.

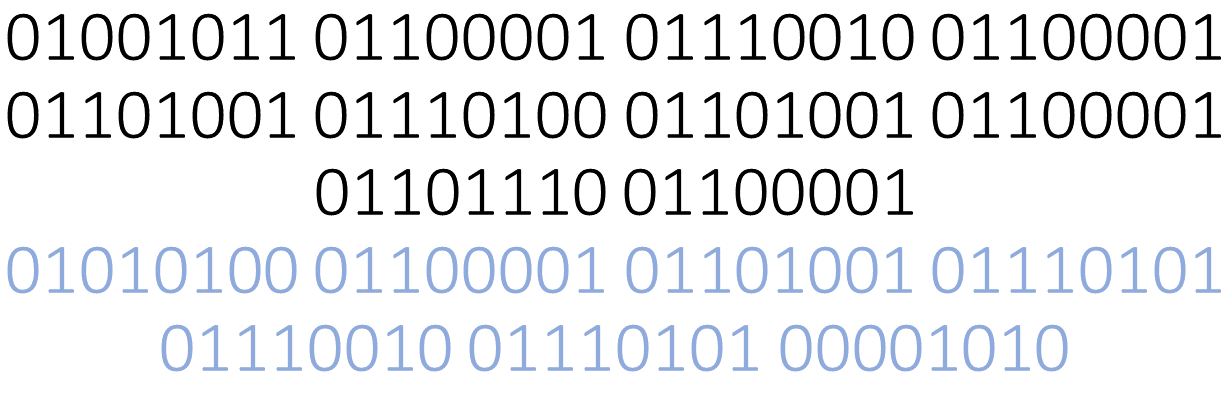

Indigenous thinking of the digital ecosystem

This information is sourced from several presentations (Taiuru, 2015b, 2015c, 2015d).

Below is a way of thinking of the digital ecosystem and how Māori data travels and is stored in that ecosystem. This will raise more awareness of the importance to Māori of data and how it travels in the digital eco system.

Internet – Ipurangi Internet is equivalent to the whole world. The Internet infrastructure (land, sea, air) in New Zealand is “Te Ao Māori – The Māori world”.

Internet from Southern Cross Cable: A vein inside Tangaroa Connects Papatūānuku and Tangaroa Māori belief is that seafood near the cable can not be eaten

Fibre and cables: Veins inside Papatūānuku. Consideration of significant land areas when laying cables

Wireless: Sending knowledge via Tawhirimatea. Consideration: What kind of knowledge is it?;Is there sacred knowledge?;Will there be a wifi connection next to a sacred land area?; Digital Data is sent in packets through the air and through human bodies, resulting in an infringement of sacred knowledge.

Network Providers/iwi: Network Providers are the same as Iwi.

Networks/Hāpū: Corporate/Education/Organisation and personal networks are the same as traditional Māori hāpū.

Web sites/Whānau Web sites are the same as whanau.

Computers / Rorohiko: Computers are the people. Systems and apps are the body parts that make the people. Systems and apps need whakapapa and appropriate names.

Firewall and AntiVirus / Pā A p ā is a fortified village that protected all members of a family, hāpū and Iwi who sought safety. Often more than one and there were traps and decoys to protect the pā.

Social media and crowd sourcing /Marae: A marae is where Iwi, h ā p ū, whanau and tangata met to discuss various topics, catch up with friends and to generally create a large social gathering. Māori culture are accustomed to crowd sourcing and open planning

Mobile phone/ Waea Pūkoro: Traditional Māori musical instrument called a Purerehua created sounds in the wind and was used for communication.

Commercial and Proprietary software and systems could be referred to as colonial tools.

Proprietary systems and software: International conglomerates take Intellectual Property that has remained within traditional Māori knowledge for centuries. Māori cannot understand the environment Help and information are not readily available. A user pays for the right to access their own information

Māori Data flow: Wifi, microwave beaming Māori knowledge in the airwaves over other tribal lands, through people and buildings, off river beds etc.; Information flowing in cables all over the world; Tapu information in our food sources and ocean

Tikanga Test

Hirini Moko Mead (2003) has developed a framework using Tikanga Maori and Mātauranga Māori to assess contentious issues to find a Maori position on these issues. This test and the proposed models below should form the basis for any decision-making process involving Māori data.

Hirini Moko Mead’s framework uses five tests by which you can assess a Māori stance to an issue. These tests are:

Test 1: The Tapu Aspect – Tapu relates to the sacredness of the person. When evaluating ethical issues, it is important to consider whether there will be a breach of tapu, if there is, will the gain or outcome from the breach be worth it.

Test 2: The Mauri Aspect – Mauri refers to the life essence of a person or object. In an ethical context, one must consider whether the Mauri of an object or a thing will be compromised and to what extent.

Test 3: The Take-utu-ea aspect – Take (Issue) Utu (Cost) Ea (Resolution). Take-utu-ea refers to an issue that requires resolution. Once an issue or conflict has been identified, the utu refers to a mutually agreed upon cost or action that must be undertaken to restore the issue and resolve it.

Test 4: The Precedent aspect. This refers to looking back at previous examples of similar issues that have been resolved in the past. Precedent is used to determine appropriate action for now.

Test 5: The Principles aspect. This refers to a collection of other Maori principles or values that may enhance and inform an ethical debate. Issues such as those listed in the Community-Up Model: manaakitanga, mana, now, tika and whanaungatanga (Smith & Cram, 2001) or the Māori Data Ethical Model (Taiuru,K. 2018).

Māori Data Ethical Model

Community-Up Model (Smith & Cram, 2001) established a model to work with. This model is a further expansion to be applicable and to act as a guide to researchers, statisticians and others how manage data more ethically from a Maori perspective (Taiuru, 2018).

- Kaitiakitanga

- Kawanatanga

- Kotahitanga

- Manaakitanga

- Maoritanga

- Maramatanga

- Rangatiratanga

- Tohungatanga

- Wairuatanga

- Whanaungatanga

References

Archie, C. (1995). Maori sovereignty: the Pakeha perspective. Auckland, N.Z: Hodder Moa Beckett.

Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Maori culture. Auckland, N.Z: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, G. (2012). Kaupapa Maori research: Epistemic wilderness as freedom? New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2), 64-73.

Hudson, M. (2018). Social License: A Maori’s Perspective. In M. R. t. M. D. S. Network (Ed.).

Hutchings, J. P. R. (2005). The Obfuscation of Tikanga Maori in the GM Debate.

King, M. (1978). Tihe mauri ora: aspects of Maoritanga. Wellington: Methuen New Zealand.

Mead, S. M. (2016). Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. Wellington, N.Z: Huia.

Prendergast-Tarena, E. R. (2015). Indigenising the corporation: indigenous organisation design : an analysis of their design, features, and the influence of indigenous cultural values : a thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management at The University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Taiuru, K. (2015a). Definition: Digital Colonialism. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Taiuru, K. (2015b). He Taonga te digital data: A tikanga perspective. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Taiuru, K. (2015c). Impacts and Considerations for Indigenous Populations using Open Source. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Taiuru, K. (2015d). The Internet infrastructure and technologies from an Indigenous perspective: Comparing Māori traditions and genealogies. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Taiuru, K. (2018). Māori Data Ethical Model. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Tau, T. M. (2001). The death of knowledge: ghosts on the plains. The New Zealand Journal of History, 35(2), 131.

Williams, D. V., & New Zealand. Waitangi, T. (2001). Mātauranga Māori and taonga: the nature and extent of Treaty rights held by iwi and hapū in indigenous flora and fauna, cultural heritage objects, valued traditional knowledge.

[1] https://www.data.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Data-Strategy-and-Roadmap-Oct18.pdf

[2] https://www.tuhoronuku.com/store/doc/aug11_maraehapuwainumbersfordompresentation-final.pdf

[3] https://ngaitahu.maori.nz/hapu/

[4] https://www.data.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Data-Strategy-and-Roadmap-Oct18.pdf

Leave a Reply