Introduction

What is a Taonga

Tikanga

–Whakapapa

– Mauri

– Wairua

Traditional Knowledge

Loss of customary knowledge

Data Sovereignty of DNA samples

Digital Colonisation

Tikanga Test

Links of Interest

References

Introduction

This paper was originally written in direct response to the Law Commission’s public consultation (and forms a part of my public submission) on the use of DNA in criminal investigations. It is intended to raise issues of DNA and genomic ownership and customary Māori rights. By highlighting customary issues, it is possible that all New Zealander’s DNA could be better protected with better privacy. It could be read in conjunction with my paper Data is a Taonga.

For the purposes of this paper, DNA is referred to as Māori genetic data. Māori Genetic Data is genetic data that is held by Māori, extracted from a taonga species or ira tangata, contains or represents any Māori biological material that can trace whakapapa to Ranginui and Papatuanuku and therefore Io.

Western scientific research proves that all species: fish plants, trees etc. all share large amounts of DNA with humans. Research also proves that humans come from a few common ancestors. Traditional Māori knowledge verifies this western scientific research. Traditional Knowledge states that all living things and natural objects have a direct whakapapa that goes back to Rangi and Papa via Io.

Tane Mahuta and his descendants created humans, birds, flora and fauna, insects and many other creatures. Tane Mahuta’s brother Tangaroa and his descendants created sea creatures. Therefore, all genetic data contains whakapapa of all tipuna and is a taonga.

Māori Data is a taonga and a highly valuable strategic asset to Māori (Taiuru, 2018). Mana Raraunga the Māori Data Sovereignty Network state that Māori Data should be subject to Māori governance, therefore Article 1 of the Treaty (Hudson, 2018). I argue that Genomic Māori data should be subject to Māori governance and tribal sovereignty that enables the realization of Iwi aspirations.

Governments and commercial entities consider genomics to be important. Internationally genomes have become a new commodity that is sold and traded on markets. Because of the western perspective that genomes are owned by the individual and can be traded and researched, genomes are treated as the new terra nullius not as a taonga that DNA is.

What is a Taonga

Before discussing why a genome is a taonga, recognised definitions of the term taonga need to be considered.

- The term taonga defies any exhaustive definition, and in summing up the findings of a number of Tribunal reports the Tribunal stated in the Petroleum Report of 2003 (The Petroleum Report (WAI 796, 2003) at [5.3].)

Though the term has a number of other more mundane meanings, successive carefully reasoned reports of the Tribunal over many years now have come to treat ‘taonga’, as used in the Treaty, as a tangible or intangible item or matter of special cultural significance. - The courts have also acknowledged that the status of taonga applies to the tangible and intangible, accepting both language and familial organisation as examples of intangible taonga. See in respect of language see New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General HC Wellington CP942/88, 3 May 1991; New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 (CA) and [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC); in respect of familial organisation see Barton-Prescott v Director-General of Social Welfare [1997] 3 NZLR 179 at 184.

- Lord Woolf of the Privy Council followed the approach of the Court of Appeal as well as the Tribunal in the final Broadcasting Assets decision stating:

The Maori language (Te Reo Maori) is in a state of serious decline. It is an official language of New Zealand, recognised as such by the Maori Language Act 1987. It is “a highly prized property or treasure (taonga) of Maori” (Cooke P [1992] 2 NZLR 576, at p 578 in the Court of Appeal) and it is also part of the national cultural heritage of New Zealand. New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney General [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC) at 513. - New Zealand courts have also discussed the notion that taonga may not necessarily be held by Māori, made by Māori or hold any Māori content or association. See Jacinta Ruru’s discussion of the cases of Page v Page (2002) 21 FRNZ 275 and Perry v West HC Auckland CIV-2002-404-002114, 15 December 2003 in Jacinta Ruru “Taonga and Family Chattels” [2004] NZLJ 297.

The definitions of a taonga used by the Waitangi Tribunal mean that any taonga is protected under the guarantees in article 2 of the Māori text of the Treaty of Waitangi which states:

The Queen of England agrees to protect the chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures. But on the other hand the Chiefs of the Confederation and all the Chiefs will sell land to the Queen at a price agreed to by the person owning it and by the person buying it (the latter being) appointed by the Queen as her purchase agent.

It is important to note here that some claims to the Waitangi tribunal regarding taonga have been unsuccessful and there is not yet a claim for data as a taonga.

Tikanga

Genetic material, DNA and Genomes are biological whakapapa. DNA and Genomes have Mauri, Wairua and Whakapapa.

Whakapapa

Whakapapa in its simplest sense is genealogy, in a wider sense whakapapa attempts to impose a relationship between an iwi and the natural world. Moreover, whakapapa is a metaphysical framework constructed to place oneself within the world (Tau, 2003). Whakapapa is one of the most prized forms of knowledge and great efforts are made to preserve it (Barlow, 1991).

Mauri

Traditional knowledge also tells us that every natural object and living thing has a spiritual aspect. If we sit down, our mauri sits down with us and some mauri can be left behind if not considered. Likewise, a photograph of a person contains the mauri of the persona. Hence, photos of the dead are tapu. Therefore, any DNA sample that is stored and manipulated will still contain the mauri of the person in the same manner as a photo.

In te ao Māori, information is tapu and contains the tapu of the person it is about. Once you learn new knowledge it becomes a part of your mauri. Hence knowledge was not always provided and could not be provided. Because of this, knowledge has been taken by academics and governments without permission.

John Rangihau explains the process of gathering and learning new information:

I talk about mauri and some people talk about tapu. Perhaps the words are interchangeable. If you apply this life force to all things – inanimate and animate – and to concepts, and give each concept a life of its own, you can see how difficult it appears for older people to be willing and available to give out information. They believe it s a part of them, part of their own life force, and whey they depart they are able to pass this whole thing through and give it a continuing character. Just as they are proud of being able to trace their genealogy backwards, in the same way they can continue to send the mauri of certain things forward (King, 1978).

Some Māori will say genomes have no Mauri. If you consider a Māori world view and consider the statement from John Rangihau above. Then, because genome data originated from a person, or other living thing in the Māori world, the data does have a mauri.

Wairua

At its core, wairua refers to the spirit of a person as distinct from both the body and the mauri (Benton, Frame, Meredith, & Te Mātāhauariki, 2013). Wairua lives in and is a part of a DNA. Therefore, once DNA has been taken, that person or other species wairua has also been taken and is stored in a foreign system.

The integrating force of life is the wairua; wairua envelopes the heart, liver, lungs, kidneys, intestines, blood, muscles, ears, it is the cultivator, caretaker and integrator of all these things, so they stay in that place, within the part of the body… The wairua and its properties are also revered because they are he cause of man’s sancity; if the wairua did not disengage itself, man would not die; and if every part (of the body) that was cleansed of tapu was held onto by the wairua, life would not end ( Elsdon Best cited in Benton, Frame, Meredith, & Te Mātāhauariki, 2013).

The heavy influence of Christianity has seen the word Wairua adopted to be more more appeasing to Christianity. The term wairua was adopted in biblical translations to cover terms translated in English as ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’ (Benton, Frame, Meredith, & Te Mātāhauariki, 2013).

Traditional Knowledge

Traditional stories contain many warnings about genome editing and manipulation and the dangers if we are not careful. I note some Iwi stories differ in names, but they are still relatively the same.

Tane Mahuta created a woman with the help of his brother Tangaroa ripping off part of his chest. But in the process of making the woman, he inadvertently created species of the forests. But he also created monsters and other evil species in the process.

Tane Mahuta’s brothers, Peketua, Punaweko and Hurumanu created Tuatara, Land birds and Sea birds by fashioning clay into an egg. They then sought advice from Tane Mahuta who told them to endow the clay egg with life. Peketua produced the tuatara from the shell that he had fashioned from clay. Hurumanu created sea birds and Punaweko created land birds.

Maui in an angry rage turned his brother into a dog.

Tipuna Māori understood that body fluids were tapu. One of the most common forms of makutu is that in which a medium is used in order to connect the spells of the tohunga with the object to be acted upon by them. This medium, termed “ohonga” and “hohonga,” when main is the object, is usually a fragment of a persons clothing, a lock of hair, a portion of spittle, or a portion of earth on which he has left his footprint (Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1868-1961 Volume 34, 1901 pg 75). Tipuna Māori also considered knowledge to be tapu.

Tipuna Māori often gave ethnographers tapu information for paper medium created by metal plates. The distribution was severely restricted to those who could purchase a book. Informants had no idea of the Internet and information flow and speed of that flow. Genome Data today faces a similar fate. Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence are future risks that will affect Māori genome Data in ways that no one has yet realized the potential impacts to Māori and Iwi are limitless.

Loss of customary knowledge

All Māori are born with whakapapa but not all Māori are Māori practitioners. There is no one Māori world view, in as much as there is no one New Zealander world view. Māori are diverse as a people.

Māori societal structure is made up of descendants from the original waka that arrived in New Zealand. Then whānau who make up a larger hapū who are associated to the larger Iwi. Each whānau, hapū and Iwi have their own lore’s and values, though not so dissimilar as to be totally foreign to each other. StatsNZ recognise 137 Iwi. There is no records of how many hapū exist. Ngā Puhi according to Tūhono have about 278 hapū. Ngāi Tahu have 136 hāpu.

Hirini Mead, (Mead, 2016) asserts that in 1979 it was obvious that few people really understood tikanga, and this included our own people. Tā Timoti Karetu also laments the loss of kawa on the marae in 1978 when he stated “it is more important to take a stand now and rescue what we can from those few kaumatua still living before the take their knowledge with them to the grave (King, 1978).

The loss of traditional knowledge, tikanga and kawa is likely due to the facts that Māori culture has been integrated into European culture for over several hundred years by colonisation, intermarriage, introduced and forced religion, urbanisation, legislation and educationalists encouraging the move away from Māori culture and government imposed assimilation.

There has also been several hundred years of heavy missionary influence introducing new religions that taught that Māori religious beliefs were bad and incorrect. Many Māori adapted to these new religions or created new religions to get the best of both religions, leaving behind their traditional knowledge systems and beliefs. Māori had many forced intermarriages into other different cultures through the colonization process. There were also customary intermarriages between hapū and Iwi.

In addition to the loss of traditional Māori knowledge, Māori academics have institutional boundaries they must work within. Western sciences and knowledge institutions do not recognise traditional knowledge, therefore how do Māori academics publish material about tikanga and mātauranga Māori? Cooper (2012) states that Māori knowledge has been cast by Western science into an epistemic wilderness, and Māori are regarded as producers of culture rather than knowledge.

The position of Kaupapa Māori is paradoxical. It must stand aloof from the concerns of science and centre Māori epistemologies as a starting point for research. At the same time it must critically engage Western knowledge and production practices as part of its decolonizing and transformational strategy (Cooper, 2012).

Government consultations have often misused Māori consultants to speak against Māori world views when there are no clear guidelines (Hutchings, 2005). In 2018, MBIE initiated the Plant Variety Rights Act 1987. Part of the submission asked if Taonga Species were adequately being protected. Yet, by their own admission they did not know what a Taonga Species was and referred to the WAI 262 Claim Report (Personal correspondence). This is becoming increasingly common for governments to refer to WAI 262, despite no government commitment to fulfill the recommendations.

Data Sovereignty of DNA samples

Genetic material can be and is often converted into digital data and shared on the Internet and with other researchers and scientists. The extinct Huia and the Tuatara are examples of Taonga species that have been digitized and shared on the Internet. Human genomes are also digitized and shared in the same manner.

When researchers and corporates analyse DNA for ancestry analysis, digitize Māori data and information without permission or consultation of the Iwi, they have breached traditional Māori customary rights and beliefs. It is too late to prevent the digitization and dissemination of taonga in the web and in digital repositories, but it is not too late to be considerate of customary rights/beliefs and to lessen any future impacts.

If we consider the early colonisers and Christians to New Zealand who normalized the practice of collecting human body parts such as mokomokai (preserved heads). Society and government did not see anything wrong with this barbaric practice. Now, It is no longer socially acceptable. Only recently has repatriation of these human remains began. With the same knowledge learnt by history, we now must contemplate how many years will go by till Māori repatriate their genome data?

Colonisation

Digitising DNA data is recognised in principles 1, 2, 3 and 5 of the definition of Digital Colonisation (Taiuru, K. 2015):

- 1. A dominant culture enforcing its power and influence onto a minority culture to digitize knowledge that is traditionally reserved for different levels of a hierarchical closed society, or information that was published with the sole intent of remaining in the one format such as radio or print.

- 2. A blatant disregard for the ownership of the data and the digitized format, nor the dissemination.

- 3. Digital data that becomes the topic of data sovereignty.

- 5. Conglomerates and government who use their influence to digitize data without consultation.

Tikanga Test

Hirini Moko Mead (2016) developed a framework using Tikanga Maori and Mātauranga Māori to assess contentious issues to find a Maori position on these issues. This test and the proposed models below should form the basis for any decision-making process asking if DNA is a Taonga.

Hirini Moko Mead’s framework uses five tests by which you can assess a Māori stance to an issue. These tests are:

Test 1: The Tapu Aspect – Tapu relates to the sacredness of the person. When evaluating ethical issues, it is important to consider whether there will be a breach of tapu, if there is, will the gain or outcome from the breach be worth it.

Test 2: The Mauri Aspect – Mauri refers to the life essence of a person or object. In an ethical context, one must consider whether the Mauri of an object or a thing will be compromised and to what extent.

Test 3: The Take-utu-ea aspect – Take (Issue) Utu (Cost) Ea (Resolution). Take-utu-ea refers to an issue that requires resolution. Once an issue or conflict has been identified, the utu refers to a mutually agreed upon cost or action that must be undertaken to restore the issue and resolve it.

Test 4: The Precedent aspect. This refers to looking back at previous examples of similar issues that have been resolved in the past. Precedent is used to determine appropriate action for now.

Test 5: The Principles aspect. This refers to a collection of other Māori principles or values that may enhance and inform an ethical debate.

Summary

All biological samples including DNA and Genomes of species that whakapapa to Ranginui and Papatuanuku contains whakapapa, wairua and mauri, therefore are tapu and are a taonga. These genetic taonga should be recognized in Article 1 of the Treaty of Waitangi. If recognised as a Taonga, this would also give all New Zealanders protection that no one in the future will claim ownership of their DNA and genome data.

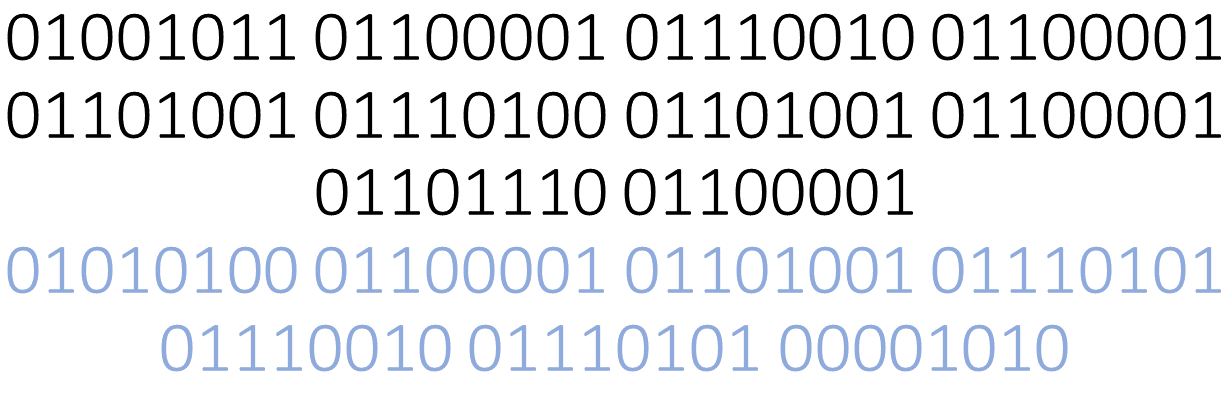

Often DNA and Genomes are digitized and turned into computer readable code. Despite a different appearance, this digital data is a taonga that still contains wairua, mauri and whakapapa. Therefore it is tapu. This is digital colonisation and Data Sovereignty concerns need to be considered in addition to customary Māori rights and beliefs.

Links of interest

A summary of Māori issues from the Law Commission report (2018) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/DNA

He taonga te raraunga? Is data taonga? (2018) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57nFcXAycFg

Dangerous Game of DNA Testing (2017) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/the-dangerous-game-of-dna-testing/

Data is a Taonga (2018) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/data-is-a-taonga/

He Taonga te digital data: A tikanga perspective https://www.taiuru.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/He-Taonga-te-digital-data.pptx

References

Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Maori culture. Auckland, N.Z: Oxford University Press.

Benton, R., Frame, A., Meredith, P., & Te Mātāhauariki, I. (2013). Te Mātāpunenga: a compendium of references to the concepts and institutions of Māori customary law. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Cooper, G. (2012). Kaupapa Maori research: Epistemic wilderness as freedom? New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2), 64-73.

Hudson, M. (2018). Social License: A Maori’s Perspective. In M. R. t. M. D. S. Network (Ed.).

Hutchings, J. P. R. (2005). The Obfuscation of Tikanga Maori in the GM Debate.

King, M. (1978). Tihe mauri ora: aspects of Maoritanga. Wellington, New Zealand.

Mead, S. M. (2016). Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values (Revis ed.). Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Taiuru, K. (2018). Data is a Taonga. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Taiuru, K. (2015a). Definition: Digital Colonialism. Retrieved from https://www.taiuru.maori.nz

Tau, T. M. (2003). Ngā pikitūroa o Ngāi Tahu: The oral traditions of Ngāi Tahu. Dunedin, N.Z: University of Otago Press.

Leave a Reply