Presentation to the Digital Justice – Emerging Technologies, Methods and Research on September 11 2020. Presentation here.

Abstract

An introduction to Māori and Indigenous Data sovereignty and digital colonisation. The presentation starts with a traditional Māori society view of Data, customary ownership values, Treaty of Waitangi values and Indigenises digital data to show the importance of data in a modern digital systems and society. The need to consult with Māori and Indigenous Peoples at all levels of policies, legislation and development of any systems that contain Maori data, including with Artificial Intelligence to avoid unconscious bias and negative consequences.

Using the key messages in the presentation, two scenarios are discussed. A hypothetical example of a potential issue with The Budapest Convention and Māori Data Sovereignty and a real life example of a New Zealand Covid19 Tracing app that caused concerns within the Māori community due to data sovereignty and trust issues that could have been avoided with Māori community consultation.

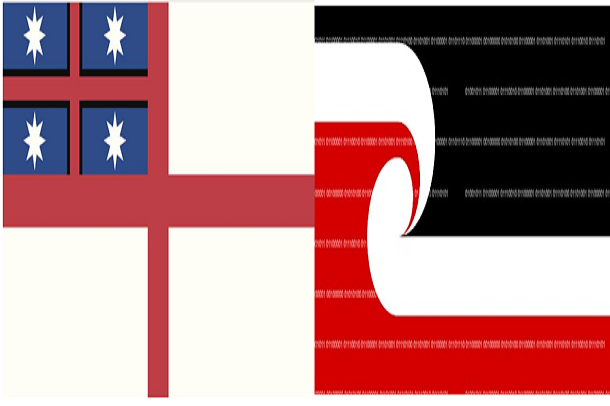

Treaty of Waitangi overview

The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. It was first signed, on 6 February 1840. The Treaty is an agreement written in Māori and English, that was made between the British Crown and Māori chiefs. These rights and obligations are found in New Zealand legislation called the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975.

The Māori version differs to the English version. So we refer to the Māori version as Te Tiriti and the English version as The Treaty of Waitangi.

Māori Data sovereignty has its foundations in Te Tiriti/Treaty of Waitangi Article II.

Article II provides all Māori the exclusive right of their full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties which they may collectively or individually possess so long as it is their wish and desire to retain the same in their possession.

Article II of Te Tiriti states “Queen of England agrees to protect the chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures.

Article II English:

Her Majesty the Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the Chiefs and Tribes of New Zealand and to the respective families and individuals thereof the full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties which they may collectively or individually possess so long as it is their wish and desire to retain the same in their possession; but the Chiefs of the United Tribes and the individual Chiefs yield to Her Majesty the exclusive right of Preemption over such lands as the proprietors thereof may be disposed to alienate at such prices as may be agreed upon between the respective Proprietors and persons appointed by Her Majesty to treat with them in that behalf.

Article II Translation:

The Queen of England agrees to protect the chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures. But on the other hand the Chiefs of the Confederation and all the Chiefs will sell land to the Queen at a price agreed to by the person owning it and by the person buying it (the latter being) appointed by the Queen as her purchase agent.

Article II relevance to Māori Data

The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti provide for these three principles commonly recognised by government and first outlined in the Royal Commission on Social Policy (1988).

In relation to Data projects, systems, policies, legislation etc, these three principles that cover the need for: Co-Governance, Co-Design and Co-Innovation.

1.Partnership: interactions between the Treaty partners must be based on mutual good faith, cooperation, tolerance, honesty and respect

- Participation: this principle secures active and equitable participation by tangata whenua

- Protection: government must protect whakapapa, cultural practices and taonga, including protocols, customs and language.

It is essential that in order to recognise Māori Data Sovereignty rights and be a good treaty partner that these principles are observed and respected in good faith.

By using these treaty principles, the system will be less likely to use Bias data or produce a system that while the developers may have had the best of intentions, could prevent the system negatively impacting on Māori. I will discuss a real life case and a hypothetical case at the end of this presentation.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007.

It is also imperative to consider, that in New Zealand the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007 which New Zealand ratified in 2010.

The UNDRIP is a comprehensive international human rights document on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. It sets out the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, wellbeing, and rights of the world’s indigenous peoples.

Its 46 articles cover all areas of human rights and interests as they apply to Indigenous Peoples. The following 21 articles are generally applicable to Indigenous Data. Depending on the Data there may be others. Articles of interest to Māori Data are: 1,2,3,4,7,8,11,15,18,19,32,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46

Pre colonisation perspectives of Data

Māori society was always, and still to a large extent a knowledge society with experts in sciences, religion, astrology, navigation, spirituality, arts, knowledge, history, medicines, social issues and many more disciplines.

Traditional Māori society was hierarchical with a myriad of rules and a justice system for breaking those rules. One of those rules was that knowledge and information was only to be shared under strict circumstances and within an acknowledged hierarchy of appropriate people ascertained by genealogy who after long and strict initiations in within learning schools within their own clan or tribe where specific people trained in certain knowledge areas.

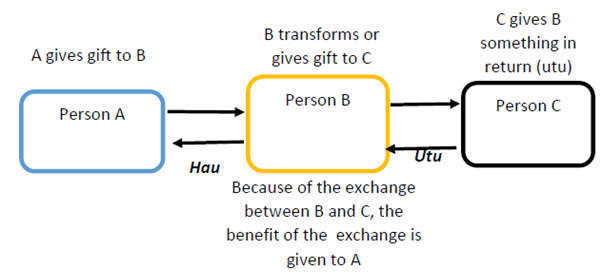

It is a customary belief that when you share knowledge with people, that the person who you are sharing information with, then acquires a spiritual part of you. From a western perspective, if you imagine a thought of a person in your mind, you have no control of that thought existing. No one else can see it, but you know it is in your brain and a part of you. Therefore, in a customary Maori perspective that Māori Data contains wairua, mauri, it becomes a form of genealogy of whakapapa and therefore becomes sacred or tapu.

Likewise, once Māori Data is in a system, that system becomes part of the people the data is about. An AI system has many more cultural complications.

In New Zealand the government and museums are aware of the need to repatriate physical property but it is still not understood that data is property, therefore no different.

This is the reason Māori Data is a Taonga as stated in Article II of Te Tiriti/Treaty. Māori Data from a western perspective is also a property and a commodity and therefore all principles of Te Tiriti are applicable.

What is Māori Data

Māori as with many other Indigenous Peoples are one with the land and the water. Without the natural resources we are not Indigenous Peoples. History, customs and knowledge bind us together is a complex genealogical hierarchy.

Māori custom does not see a difference between our land and our data. Our data has the same sort of connections as a land does, but it is just a different format. To protect our data and we need to recognise that it is collectively owned by whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations. Not one individual can own our data, or should own our data. No non Māori individual or group can own Māori data.

There are also the cultural considerations of the origins of the data, the mauri of the data, what rights does the person who gave that data have, what rights do they actually give the person who is collecting it or the organisation? This also creates issues about Maori data about the living being stored with Maori data about the dead.

Māori Data is information or knowledge, in any format or medium, which is about, from, produced by Māori, describes Māori and the environments Maori have relationships with, made by Māori or contains any Māori content or association or may affect Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations either collectively or individually (Taiuru,K. 2020).

Māori Data Sovereignty – Common Definition in New Zealand

Māori Data Sovereignty supports tribal sovereignty and the revitalisation of Maori and Iwi aspirations. (Te Mana Rauranga Maori Data Sovereignty Network)

Data Sovereignty is sometimes called jurisdictional risk. Jurisdictional risks occur where data is subject to the laws of the country where cloud services providers store, process, or transmit data. ‘Data sovereignty’ is often used interchangeably with jurisdictional risks’.

Rights of Indigenous data sovereignty and the need for collective consent are now being recognised with in the UN. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy has been engaged with indigenous data sovereignty. The Special Rapporteur’s Report on the work of the Big Data Open Data Taskforce in October 2018 explicitly addresses indigenous data sovereignty and Indigenous Peoples’ inherent sovereignty over the data collected from them, about them and their resources in paragraphs 52., 72. 73.74, 75. And again in the 2019 Report from the Special Rapporteur on the Protection and Use of Health-Related Data where several definitions were introduced.

One of the issues with this definition is that Māori society is hierarchical and complex. Māori People belong to a whānau and often more than one generation can reside in one home. Multiple families form a hapū or a clan who can also belong to multiple marae. Multiple hapū form an iwi. Māori society within an Iwi all closely interact.

While all Māori people come from at least one Iwi, most do not participate with one or more of their iwi. Many Iwi are now corporate entities with corporate policies as opposed to traditional tribal values. One example is Ngāi Tahu, in 2018 it had over 54,000 registered members but less than 10 % participated in tribal matters.

Maori tribes are also not sovereign nations and are typically legal structures such as Trusts and companies.

This definition sets the precedence for the government to consult with its Iwi partners, typically the Iwi Chairs forum a collective of some Iwi who do not necessarily have the digital expertise not the breadth of consultation required to engage in a wider Maori society.

Another issue with this definition is based on the 2013 Census data, 20% of Maori do not know their iwi.

Māori Data Sovereignty – a modified definition.

This definition considers all of Māori society and the governments treaty obligation. It does not discriminate against those who do not know their tribal affiliations.

It also recognises Māori Data Sovereignty is an Article II right and that Māori Data is a collectively or individually owned property of significant cultural, social, spiritual and economic value to Māori society. Hence, Māori Data is a Taonga.

Māori Data Sovereignty refers to the inherent rights and interests Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations have in relation to the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, dissemination, re-use and control of data relating to Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations as guaranteed in Article II of Te Tiriti/Treaty of Waitangi (Taiuru,K. 2020).

Māori Data Sovereignty – some practicable steps

Appoint a Māori Data governance Board. When appointing the board, beyond having regard to a person’s knowledge of Māori cultural values, te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori, you should consider “whether the proposed member has the reputation amongst Māori in the community, in addition to skills, knowledge, or experience to participate effectively in the Board and contribute to achieving the purposes of the Board.”

This will remove the decades long problem Māori have had in New Zealand with what we call the “Māori or brown tick box exercise”. Where any Māori person who is known by the organisation is likely to be seen as a cultural expert and asked to participate. Likewise, in recent years Māori academics have been placed in the same awkward position.

Host on shore to ensure the legislation of the land protects privacy.

Full disclosure of all facts and possible benefits and consequences. Often Māori and other Indigenous Peoples lack the technical skills to know the full consequences of what will happen to their data once it is digitised.

An example that occurred in NZ about 5 years ago with a New Zealand University and a rural iwiwith no Internet infrastructure who had a significant resource. The university wanted to digitise it and put it on the Internet. The University told the iwi that it would only remain on the university server after the Iwi expressed concerns about it being shared. As most of us will know, once on the Internet it can be copied and shared. This is what happened.

As the digital ecosystem is new and does not directly impact on Indigenous world views, it is critical to understand both the technology and traditional knowledge. We are literally creating new Indigenous knowledge as new technologies are created and impact on our worlds.

Frameworks

Because of the new knowledge that is being created, we can not rely on Māori Data Sovereignty frameworks without carefully considering them. Indigenous Knowledge can not be squeezed into a western framework. Yes, this has been occurring. Currently for Māori there are 5 different frameworks required to work with Maori Data that will consider all aspects of Maori data using the term

- Tikanga Test (Mead, S. M. (2016. Revis ed.)

- Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie, M. 1984)

- Māori Data Sovereignty Guidelines (Te Mana Raraunga, 2018)

- Crown engagement with Māori Framework and Engagement Guidelines (Te Arawhiti 2019)

- Māori Data Ethical Framework (Taiuru, K. 2020).

- Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and Māori Ethics Guidelines for: AI, Algorithms, Data and IOT (Taiuru,K. 2020)

Digital Colonisation

Some basic principles of digital colonisation are below. Essentially, using the treaty principles and full disclosure of why you want to digitise the data, what impacts there are, biases, benefits, ownership issues etc all need to be considered. Otherwise, there is a risk for bias data that could discriminate against Maori or break trust and relationships.

- Digital colonialism deals with the ethics of digitizing Indigenous data and information without fully informed consent.

- Digital colonialism is the new deployment of a quasi-imperial power over a vast number of people, without their explicit consent, manifested in rules, designs, languages, cultures and belief systems by a vastly dominant power (Renata Avila, 2017).

- A new form of imperialism by technology conglomerates for commercial gains; academics and researchers to advance science, technology and research (Taiuru 2017).

- Data colonialism is an emerging order for the appropriation of human life so that data can be continuously extracted from it for profit (Ulises A. Mejiasand Nick Couldry. 2019).

Māori Data Governance

As practitioners we know that in the western world data being anonymised. For non Indigenous Peoples this where it stops as there are no privacy concerns and no way to identify the data.

Māori Data has a history, genealogical connections and a spiritual connection to it. Similar to Māori art and other traditional customs that appear to unlearned people as art or music, is rich in data to a learned person.

It is also important that any data project or initiative is co governed, co designed, co-created and co- managed in partnership with Māori. In New Zealand, it is essential that any Data project has a Treaty of Waitangi clause. As we have seen in New Zealand, the best of intentions with Data lead projects can fail Maori and in some instances discriminate Maori.

Māori Data Governance is the right of Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations to autonomously decide what, how and why Māori data are collected, stored, accessed and used.

It ensures that Māori data reflects Te Tiriti/Treaty Principles. (Taiuru,K. 2020).

Scenario 1 Hypothetical Māori Data Sovereignty issue with the Budapest Convention

New Zealand is consulting with the public re the Budapest Convention.

As a layperson of the law, I think the Budapest Convention is essential to protect our society. I also realise there is a grey area of Maori data sovereignty and co operating with law enforcement agencies.

The first concern is that as I have already discussed earlier, Māori consider their data is a taonga, a treasure. As a country that spends a significant amount of money repatriating Maori artifacts that are considered a taonga by Maori, it is an interesting point of discussion that the New Zealand Crown does not have any significant engagement with Maori regarding their digital taonga.

My advise is that you should always have a suitably qualified Indigenous perspective or perspectives available for any data related legislation, consultation, policies and strategies.

In terms of the Budapest convention there are some real risks of data being taken in an investigation and sent offshore. Marae are increasingly being installed with networks. One example could be a pedophile using a communal computer to share images offshore. Then a request is made for that server. Despite the fact the server is likely to have a significant amount of photos of families, sensitive business information and transactions and a vast amount of sacred information, who decides what is relevant and what is not? This situation is likely not to occur in a western situation.

Scenario 2 A real life example. Covid 19 app tracer

The world simply did not have a precedence for Covid19. No one will ever know if there was time and if Maori were consulted re the Covid 19 tracing app if the following issues could have been rectified.

An important lesson for all Indigenous Peoples, policy makers, legislators etc, is to work in partnership and create frameworks and partnerships in anticipation for any data driven system.

In this case, had Māori and government worked together earlier , the developers would have been alerted to some key facts ts not considered in the design:

- Data is stored in an AWS data center in Australia. While only some information is, this is still a concern for many Māori. Data Sovereignty issue.

- The registration process required an Internet connection.

- The system required one person per device with an email address. It is common for a digital device to be shared with one Maori family unit that consist of multiple generations.

- The system did not recognise NZ’s official language Māori in email address

- Based on govt data, Māori rank highly in domestic violence rates, yet there was no protection for such people in the app.

This has resulted in a number of communities of Māori who refuse to use the app and simply can not. Had consultation with Māori occurred early, and co-design this would not have been an issue.

- Māori Data Sovereignty Rights for Well Being (September 25, 2019) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-data-sovereignty-rights-for-well-being/

- Māori ethics associated with AI systems architecture (October 17 2019) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-ethical-considerations-with-artificial-intelligence-system/

- Māori ethics associated with AI systems architecture (September 14, 2019) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-ethics-associated-with-ai-systems-architecture/

- Māori Data Sovereignty Rights for Well Being (September 25 2019) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-data-sovereignty-rights-for-well-being/

- Submission on Government algorithm transparency and accountability https://www.taiuru.co.nz/submission-on-government-algorithm-transparency-and-accountability/

- Treaty Clause Required for NZ Government AI Systems and Algorithms https://www.taiuru.co.nz/treaty-clause-required-nz-government-ai-systems-and-algorithms/

- Indigenising knowledge of Telecommunications and Smart Phones (July 23, 2019 https://www.taiuru.co.nz/huia/

- Māori cultural considerations with Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (June 21, 2019) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/ai-robotics-maori-cultural-considerations/

- Why Data is a Taonga: A customary Māori perspective. (November 2018) http://taiuru.co.nz/data-is-a-taonga

- Definition: Digital Colonialism (July 23, 2015) https://www.taiuru.co.nz/definition-digital-colonialism/

References

- Durie, M. (1984). Te Whare Tapa Whā

- Mead, S. M. (2016). Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values (Revis ed.). Wellington: Huia Publishers.

- Mejias, Te Mana Raraunga (October 2018). Principles of Maori Data Sovereignty. New Zealand.

- Taiuru, K. (2015). Definition: Digital Colonialism Retrieved from https://www.taiuru.co.nz/definition-digital-colonialism/

- Taiuru, K. (2018). Data is a Taonga. A customary Māori perspective. Retrieved from https://www.taiuru.co.nz/data-is-a-taonga/

- Taiuru,K (2020. Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and Māori Ethics Guidelines for: AI, Algorithms, Data and IOT https://www.taiuru.co.nz/tiritiethicalguide/

- Taiuru,K (2020. Māori Data Ethical Framework https://www.taiuru.co.nz/tiritiethicalguide/maori-data-ethical-framework/

- Te Mana Raraunga (October 2018). Principles of Maori Data Sovereignty. New Zealand.

- Ulises A. Mejias & Nick Couldry (2019). [BigDataSur] Some thoughts on decolonizing data.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.