This analysis uses two apps offered by Te Wānanga o Aotearoa and looks at their tikanga and privacy issues. The purpose of the article is to raise awareness of traditional knowledge being used to create new ideas to attract youth Māori to new initiatives such as education and being proud to be Māori. Their third app, a Pōwhiri app is worthy of its own analysis and is not considered here.

Some Māori find it intolerable when their culture and images are inappropriately used, used satirically with images and Internet memes. Yet if made by Māori or non Māori for a Māori organization the issues are the still the same, though maybe not as obvious to Māori.

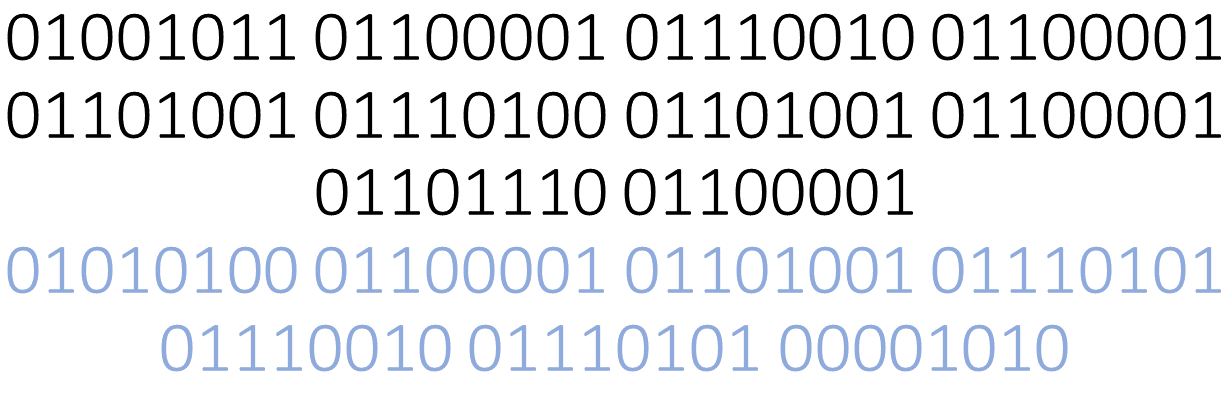

Sir Hirini Moko Mead in his second edition book ‘Tikanga’ discusses tikanga adapting to technology and how it evolves. Using my interpretation of his test to ascertain if something is tikanga offensive; I suggest that there are a number of concerns that should in the very least have a disclaimer associated with Te Wānanga o Aotearoa Facebook and SnapChat apps. There are also a myriad of privacy concerns that the app developer stated he was not concerned about, but I argue that they should be considered.

SnapChat

Te Wānanga o Aotearoa SnapChat app called 3D Tiki Filter takes the image of the Māori and Polynesian deity of fertility Tiki and imposes him into a photo wearing headphones so people can take photos with Tiki.

Using a Māori and Polynesian deity is likely to be offensive and a breach of tikanga in the same manner that a photo of Jesus Christ, Budha, Mohammed or any other religious god or leader would be offensive in a SnapChat photo.

The developer has stated that (sic) the Tiki can also represent an ancestor. I can only assume he means for people with whakapapa to Tiki, that Tiki is their ancestor.

Based on his statement, there is a different tikanga. Who is the ancestor? Unwitting people will be having a photo with a colonized representation of someone else’s dead ancestor. There is also the tapu/noa issue of a photo with a dead person.

About Tiki

This section is copied and pasted from an earlier article I write about Emoticon (Taiuru, 2017).

Hei Tiki the correct term for the pendant that is used as a necklace and often called Tiki is the personification of the deity Tiki that is known by numerous names. Tiki is a recognised deity across most of Polynesia.

Depending on the tribal area, Tiki is either the creator of man (Christian equivalent of God, noting that some Iwi have a belief in a more superior god called Io or other realms) or the first man on earth (Christian equivalent of Adam).

The tiki is a personification of Tiki the fertility deity and has many incantations associated with him to assist people to become fertile, hence why people traditionally wore a Tiki. The first Tiki was made for Hineteiwaiwa the atua of childbirth and te whare pora (weaving and female arts). The shape of the Tiki represents the human embryo. This story has variations in various tribal areas, but there is wide spread agreement that Tiki is a deity or a personification of fertility.

Historians speculate that the English and other immigrants to New Zealand increased the production of Tiki as they were in such high demand by immigrants and thus profitable to Māori. This combined with the introduction of steel axes which made the traditional pounamu adzes redundant, re-purposed the adzes into Tiki, and at a much quicker rate than was traditionally possible. Subsequently, this made Hei Tiki less valuable due to the mass production.

It is likely that the colonial desire for mass produced Tiki has seen the image of Tiki abused by marketing companies over many years causing some people to think it OK to use the image and in more recent years by Māori organisations.

Considerations

It is important to consider that Māori society and beliefs have been influenced by colonial: laws, religion and society. Not all Māori believe in our traditional cosmology and theology, with some referring to them as myths and legends or just simply dismiss them in favor of their new religious beliefs.

To be respectful to all to everyone who uses the SnapChat app, I believe that in the very least a disclaimer stating who Tiki is, would allow users to make better informed decisions for the individual to use the app or not.

It should be noted that the SnapChat filter appears to use the developers personal account and not Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, raising further privacy questions and why the Wānanga didn’t create a free account themselves to promote the project, but chose to use a non Māori owned SnapChat account.

It is questionable if the Te Wānanga o Aotearoa users of SnapChat are aware of the copyright right privileges they accept to give the American corporation when they sign up to use SnapChat. There rights include allowing SnapChat to use all of your photos in anyway they want and sharing the images with their affiliates.

It is possible that a photo with a person and Tiki could end up being used in advertising somewhere in the world and cause offence to people who identify and pray to Tiki. The lack of control and ownership of the image could create other tapu/noa issues as control and distribution of the image is not able to be controlled by the individual who took the photo.

There is also no Terms of Service with the app. It is not immediately obvious to know what personal information and phone functions the app accesses and the ownership of the app.

Kirituhi generator

Te Wānanga o Aotearoa are also offering a Facebook kirituhi generator. Kirituhi is a post colonial modern art form for non Māori to wear Māori tattoos. People with whakapapa wear tā moko.

Kirituhi can be designed by Māori and non Māori. It appears most of the users, if not all, are Māori; so the majority have whakapapa yet chose to use a kirituhi on their facial photos. According to Te Wānanga o Aotearoa Corporate Profile, 54% of students are Māori. This could be a tikanga breach and cause some people issues later on with their whānau. By wearing a kirituhi it could be argued that you are ignoring your whakapapa or being devious by pretending to be someone else.

I do not believe the generator is the same as the stencil paintings that kapa haka groups wear. Though I am not aware of the reasons of the stencils, I would assume they are to represent the group of performers. In contrast, the kirituhi app uses the same markings for anyone.

Māori have spoken out against copying peoples faces and adding kirituhi in the past. Matatini images and Tame Iti (Google image search for remaining images) are two recent examples. In Christchurch there was public outcry and then international attention about the Xmas parade using a tribe of Native Americans on a float which was seen as inappropriate. Internationally, Indigenous Peoples have spoken out against similar representations of culture such as Moana skin outfits which Amzon removed from sale. Indigenous costumes for Halloween were also removed from sale by Kmart after Indigenous Peoples complained. The kirituhi generator could be seen as crossing the line in term of cultural appropriation by allowing anyone to wear the kirituhi for entertainment and other short term purposes.

On the surface, it is not clear that this is Kirituhi being generated unless you research the facts. The kirituhi looks like Tā moko (Male face) or Moko kauae (Female Face on the chin). The kirituhu filter decides if the photo is a male or female and applies either a Tā Moko to a male or a Moko Kauae to a female.

It is argued Kirituhi is a way to bring social acceptance back to society of Tā moko, after the practice stopped largely due to the trade in mokomokai-tattooed heads, religious influences and the pressure for Māori to conform to Pākehā social norms.

Then we need to consider if this is the beginning of a new digital trade of mokomokai, by using photos with kirituhi and tā moko that will be held and used overseas with no ability for Māori to stop unauthorized usage of the photos. The digital tools being used to promote kirituhi claim full IP ownership of all data and images to foreign companies and then store the images and data in American data centers. By doing so, we lose the data sovereignty under USA laws such as the Patriots Act which allow the US government to do as they want with any digital data and information stored there.

Tikanga Test

Using Sir Hirini Moko Mead’s Tikanga test to see if something is offensive (Mead, 2016); I use the test with the kirituhi product using my own personal knowledge and prior discussions with whānau and colleagues.

Test 1: The Tapu test. Consideration as to if the topic in question is tapu.

Reply: The head is tapu. Kirituhi often contain stories that could be deemed tapu to the individual. Moko are tapu.

Test 2: The Mauri Test. Does the subject have mauri.

Reply: Wairua and Mauri are often associated with images and photos, especially of the dead.

Test 3: The Take-utu-ea or TUE test: If a breach of tapu and or mauri is established or is seen to be an issue, this step needs to be enacted upon.

Take: This test involves a discussion of everyone involved with the topic to recognise that there is a breach of tapu or that there will be a breach.

Reply: This is not clear if there is full acceptance. But a discussion should be considered. The developer claims the wānanga have done this and believe it to be noa (OK).

Utu: Once a breach of tapu has been agreed upon the most appropriate form of utu must be considered. Using one issue at a time; Consideration of who (people, gods etc) are implicated in the breach? Why the breach? Is it to harm or benefit people? Before carrying out the new deed, was there an assessment of the likelihood of damage to the well being of the people who will benefit from the results, technology or modifications?

Reply: This has not been disclosed. But there could be several gods and deities including Ruamoko and Maui and others. Again, a disclaimer should clear the matter.

Ea: The final desired state where a state of satisfaction where a sequence has been successfully closed, relationships have been restored, or peaceful interrelationships have been secured.

Reply. This has not been disclosed or able to be ascertained.

Test 4: The precedent aspect.

Is there a whakapapa to which the new event can be linked, or whether there is a model in our traditions that might help people understand the event and how to respond to it.

Reply: It is well known, and traditional stories tell us that an image and or reflection of a person is tapu. One popular story is of Maui turning himself into a bird to visit the underworld. Another of Maui turning his brother-in-law into a dog. Both stories represent manipulating an identity or image of a person. Digital images are vulnerable to being used to hide other people with such things as avatars. The modern day equivalent of the digital images with kirituhi or without.

Privacy Test

Another test is a modern day privacy test.

Test 1: Who has access to the information and data.

Test 2: What access does the app have on the device.

Reply. There are no Terms of Service with the app. It is not immediately obvious to know what personal information and phone functions the app accesses and what storage there is. This week the international media covered the Cambridge Analytica issues in the media it is fair and reasonable to ask if the wānanga are using this information directly from the app or indirectly from Facebook posts etc as a marketing campaign to future students.

Again the privacy concerns outlined would be alleviated with a disclaimer.

Conclusion

As one of New Zealand’s largest tertiary education providers and as a Māori organisation, more consideration and consultation could have occurred to give more confidence to the social media users that the apps were not in any breach of tikanga.

Using Sir Hirini Moko Mead’s tikanga tests provides enough evidence to at least say there is a breach of tikanga and that it should be discussed more and the information made available and accessible to the users to decide. The privacy test highlights shortcomings that there are no disclaimers or information for the users.

References

Mead, S. M. (2016). Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. Wellington, N.Z: Huia.

Taiuru, K. (2017). Cultural analysis of Emotiki app and why it is offensive. Retrieved from https://www.taiuru.co.nz/cultural-alalysis-of-emotiki-why-they-are-offensive/

Leave a Reply