These high level guidelines have been written by Karaitiana Taiuru who has been involved with Māori Cultural rights, Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge and assisting brands both in New Zealand and internationally for over 25 years.

Last updated January 10 2021.

The motivation to write this document is to provide an introduction to Māori cultural appropriation and some common methods to avoid it. A number of well intentioned individuals and companies in New Zealand over the recent years have suffered brand damage and personal reputation damage in addition to causing significant conflict with Māori individuals and groups due to mistakes that could have been avoided with these guidelines.

For a list of other writings about Māori cultural appropriation and knowledge by the same author please visit https://www.taiuru.co.nz/category/cultural-appropriation/

The Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand has TradeMark guides for Māori culture of which some of this content is sourced from.

Overview

These guidelines give guidance on the special considerations in New Zealand around the use of branding and products that contain an element of Māori culture, for example: a Māori word, image, or design. It is intended to provide guidance on how you can use unique aspects of Māori culture appropriately to create a brand, business opportunities, attract investment, and increase profits. By not recognising Māori culture you could unintentionally cause offence to Māori communities and be accused of cultural appropriation which will likely damage your reputation and brand.

A Māori cultural element is some aspect of the brand or product that reflects or is taken from Māori culture. A Māori cultural element could include: a Māori word or design, Indigenous (native to New Zealand) plants or birds, Māori music or dance. The Māori cultural element may be a small part of the brand or product, or it may involve the brand or product in its entirety.

There are only seven Māori cultural elements that are protected by law in New Zealand. At the time of writing, Mount Taranaki is going through a formal process for legal protection.

- Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu Vesting) Act 1997 and the 2002 Pounamu Resource Management Plan. An undertaking to return ownership of Pounamu (greenstone) back to Ngāi Tahu.)

- The haka ‘Kā Mate’ – Hākā Kā Mate Attribution Bill, acknowledging the haka as a taonga of Ngāti Toa Rangatira. Provides a right of attribution to Ngāti Toa in respect of the haka ‛Ka Mate’. Any person who publishes, broadcasts or shows a film in public featuring ‛Ka Mate’ must attribute it to Te Rauparaha and Ngāti Toa Rangatira.

- The Whanganui River in New Zealand is now recognised as a legal person – Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017

- Te Urewera, named a national park in 1954 and most recently managed as Crown land by the Department of Conservation became Te Urewera on 27 July 2014: “a legal entity” with “all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person” (section 11(1)) – Te Urewera Act 2014

- The Maori Language Act 1987/ Te Ture Reo Māori 2016 – the Māori language to be an official language of New Zealand.

- Flags, Emblems, and Names Protection Act 1981, Section 18A Unauthorised use of words and emblems relating to 28th Māori Battalion of the legisl ates and restricts the use of the words associated with the 28th Māori Battalion; Section 20 Unauthorised use of certain commercial names of the Flags, Emblems, and Names Protection Act 1981 legislates and restricts the use of the word ‘Ruakura’.

- Section 11 Māori Television Service (Te Aratuku Whakaata Irirangi Māori) Act 2003, Protection of names. Which provides protection for “Māori Television Service”, “Te Aratuku Whakaata Irirangi Māori” and any other name that so resembles those names as to be likely to mislead a person.

However, for most Māori elements, there are not explicit rules or a one-size-fits-all process to follow. These guidelines will offer an overview of how to navigate Māori elements and branding for your business, services, or products.

Examples of the type of questions considered by this guide include whether an image that draws from Māori culture could be offensive to Māori, or if a brand or product is derived from Māori traditional knowledge, plants or animals, would it be contrary to Māori values?

This guide also explains the purpose and role of these special considerations in the protection of Māori values, concepts, meanings and traditional knowledge of Māori culture, and shows brand owners how they can use Māori cultural elements in their branding and intellectual property without causing offence.

Article II of Te Tiriti is the main reference to protection Māori cultural rights by stating: “Māori are guaranteed by the Crown the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages, and all their property and treasures”.

Article 31 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which New Zealand signed in 2010, states that ‘indigenous people have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions, have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions’ and that ‘States shall take effective measures to recognise and protect those rights.’

What is cultural Appropriation

As proud New Zealanders, many of us get excited and feel proud when the ALL BLACKS perform the Kā Mate Haka, many of us sing with pride and or repetition our national anthem firstly in Māori and then in English and most if not all of our government departments have English and Māori names. But many of us have not likely stopped to consider the extent to which Māori culture enriches our everyday lives.

A pitfall for brand owners and product creators is that there is a belief that if a Māori item does not have copyright protection, then it is OK to use that Māori element. While it may be legal, it is widely recognised that the copyright laws are outdated and need to reflect Māori society (in fact all Indigenous and minoroties). This is further discussed in the Waitangi Tribunal section. By using Māori items without context or consultation, you are likely committing cultural appropriation and causing offence to Māori communities.

Cultural misappropriation, phrased cultural appropriation, is the adoption of an element or elements of one culture or identity by members of another culture or identity. This is controversial when members of a dominant culture (European New Zealander/Pākehā) appropriate from minority cultures (Māori).

Appropriation is not unique to New Zealand, it is an international issue that has been occurring for decades. Only recently have minority cultures received a voice to speak out about appropriation.

As businesses and product owners/developers ensuring you recognise cultural appropriation is being a good corporate citizen, a responsible person who has good values and good brand reputation.

In the digital age, there are also two other cultural offences you should be aware of as brand and product owners: Digital Colonialism and breaching Māori Data Sovereignty rights.

Digital colonialism deals with the ethics of digitising Indigenous data and information without fully informed consent.

Māori Data Sovereignty refers to the inherent rights and interests Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations have in relation to the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, dissemination, re-use and control of data relating to Māori, whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations as guaranteed in Article II of Te Tiriti.

Consultation

It is important to recognise that no matter how familiar you are with Māori culture; it is worthwhile spending some time researching the cultural significance of your proposed branding and intellectual property. It is also a grave mistake to assume that because a person is of Māori descent (or Pacific), that they are well versed in Māori culture.

It can be difficult to know who to consult with or to identify who has the authority to grant permission on a Māori element. There is no general rule. If engaging the services of a professional is not an option, the following are suggestions.

If your product or brand uses a Māori element that is specific to a geographical area, you should discuss the element with the local Māori group. Each geographical area of New Zealand is within the boundary of an Iwi, marae or a hapū. Appendix I has the Takoa resource which is a comprehensive listing of Māori organisations, services and businesses. Other avenues could include the Internet or your local MP’s office for more information.

If using a Māori cultural element, it is essential that you create a cultural narrative around your brand or product including the usage, your thinking and where you gained inspiration from. In Māori culture this is called ‘whakapapa’. Everything in the Māori world has whakapapa. It is also your first line of defense if someone accuses you of cultural appropriation.

Recognising a Maori cultural element

In most instances, recognising a Māori cultural element is the first step. There have been many examples in the media where the user has not recognised that a word, story, image, picture, etc. forms part of Māori culture.

A widely published example is a New Zealand brewery selecting the names HINEMOA and TUTANEKAI as brand names for a range of beers. These names were selected because they were the names of streets in the area where the brewery was based. However, the origins of these names were not researched. And if a little research had been done, then the New Zealand brewery would have found that these names are in fact the names of two well-known Māori ancestors from a hapū (clan or descent group) based on the shores of Lake Rotorua. Once the brand was put on the market, the hapū objected to the use of their ancestors’ names in association with alcohol.

If some research had been done, and the New Zealand brewery would have recognised that a significant Māori element existed in those names, then steps may have been taken to avoid the disrespect and humiliation caused..

Identify the Kaitiaki (guardian/custodian) of a Māori cultural element

Once you identify that a Māori element exists, it is important to continue that search for kaitiaki until identified. In some instances, identifying kaitiaki will be a little more difficult. But this does not mean that you should give up the search, or proceed anyway. Claiming that your search was extensive and you could not identify kaitiaki is not a defense to an objection from kaitiaki.

As in the example in the previous section, a quick Google search would have identified the true origins of the names HINEMOA and TUTANEKAI and kaitiaki of those names.

Once kaitiaki are identified, it is important to seek their consent, which may require a series of negotiations over a period of time. There may also be many aspects that require approval and involvement of kaitiaki. For example, not only the story must be accurate, but the images too.

If, at any point, you change the format of your use of the Māori element, then it is important to update the consent from kaitiaki to any revisions or changes you make.

You should also be aware that consent can be withdrawn, and so seeking consent as changes are made will only enhance your relationship with kaitiaki.

Māori world views and values

Many Māori values are related to the Māori story of the origin of the world, in the relationship between Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatūānuku (the earth mother) and their children, from whom all living things descend. All plants and animals, according to the Māori world view, share a relationship with each other.

The relationship between people and all living things is characterised by a shared origin or life principle referred to as mauri. Mauri is not limited to animate objects. For example a waterway has mauri (Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017), and a forest has mauri by virtue of its connectedness to Papatūānuku ( Te Urewera Act 2014).

Any act that undermines or disrespects mauri is therefore offensive. These values are the basis for Māori to act as kaitiaki of mauri. Values that enhance and protect mauri are: truth, correctness, directness, justice, fairness, righteousness, being true, valid, honest, genuine, sincere , affection, sympathy, charity, compassion, love, empathy.

Inappropriate associations

Associating Māori cultural elements with some types of goods and services could be considered offensive, as they may appear to make inappropriate assumptions about Māori. For example, alcohol, tobacco, vaping, genetic technologies and gambling all have the potential to devalue Māori people, culture and values.

Tapu is the basis of all considerations when considering or incorporating Māori elements into a product or name. They both have numerous meanings and references. Tapu can be interpreted as ‛sacred’, or defined as ‛spiritual restriction,’ and can contain strong rules and prohibitions. A person, object or place which is tapu may not be touched or, in some cases, not even approached.

Noa is the opposite of tapu and includes the concept of being common. Noa also has the concept of a blessing as if it can lift the rules and restrictions of tapu from a person or object. To associate something that is tapu, with something that is noa, is offensive to Māori.

Craft Beer breweries and food products both in New Zealand and around the world have been increasingly accused of cultural appropriation. Any food or beverage product that has a Māori element will need to use the Tapu and Noa principles as food and beverages are considered noa. If you add a picture of a person, Māori art, various Indigenous species or images such as Tiki to food or beverages, then the product will likley be offensive as all of these elements are considered tapu.

Māori to English translation

Some Māori words and concepts can be translated into English without risk of causing offence. However, sometimes there is another layer of meaning or understanding in relation to a Māori word that is lost when it is translated into English. For example, the word kuia could be translated as grandmother. This is accurate, but the translation does not reflect its full significance for Māori as a name used to show great respect, recognising a person’s achievements, wisdom and contribution. In this light, it would be offensive for kuia (tapu) to be associated with things like food or alcohol (noa).

Images

Māori artists often dedicate themselves to studying a specific art form. Part of this study includes learning tikanga (protocol), or the right way to do things. The work of these Māori artists is highly sought after and each piece is treated as a taonga (treasure).

When using or commissioning Māori artwork or designs, owners should consider using an artist or designer who is familiar with traditional Māori culture and tikanga to ensure that the trade mark or design is represented correctly and is culturally appropriate. Inappropriate cultural references could affect commercial success in the marketplace

Māori imagery, artwork and design

Pre-colonial Māori had no written language, so traditional knowledge was passed down through the generations through stories and visual art. Full of meaning and symbolism, traditional Māori art and design form an important part of Māori identity and culture. Large pieces, like waka (canoes) and wharenui (meeting houses), and small pieces, like weapons, vessels, tools, jewelry and clothing, all communicate a story and have meaning and significance. Each shape, colour and material was carefully selected for its cultural or spiritual meaning.

Māori attribute physical, economic, social, cultural, historic, and/or spiritual significance to certain words, expressions, performances, images, places, and things. There are many cases where it would not be appropriate to copy or use a Māori cultural element, especially a traditional one.

Tiki

The hei tiki is one of New Zealand’s most popular and recognisable Māori symbols, but also one of the most appropriated image of Māori cultre. It is culturally significant as he represents the unborn child and is associated with Hineteiwaiwa, the Māori goddess of childbirth or used as a fertility charm. Therefore, special consideration and respect for Hei tiki is required for this culturally significant cultural element.

Each Tiki is unique to a tribal area and usually to a family and an ancestor. Each tiki usually has a long history associated with it.

Images of Tiki should not be used and should never be copied.

Using a hei tiki for particular products or services unless it is a fertility product, will likely be offensive to Māori.

Traditional Māori Icons

- The koru depicts an unfolding fern frond. It symbolises new beginnings, growth and harmony

- The hei matau or fish hook depicts abundance, strength and determination. It is also said to be a good luck charm for those journeying over water.

- The manaia depicts a spiritual guardian. It has the head of a bird, the body of a man, and the tail of a fish. A manaia provides spiritual guidance and strength

- The pikorua symbolises the joining together of two people or spirits. It is also said to represent life’s eternal paths

- The toki is a stylised adze that represents strength, control and determination.

- Roimata means ‛tear drop’ and symbolises sadness or grief. It was sometimes given as a gift to comfort or console

The most distinctive features of Māori imagery are:

- curvilinear designs (contained by or consisting of a curved line or lines) as depicted in moko (tattooing), kowhaiwhai (rafter patterns), and whakairo (carving).

- rectilinear designs (contained by, consisting of, or moving in a straight line or lines) as depicted in tukutuku (ornamental paneling) or taniko (embroidery).

- designs incorporating Māori objects.

- Photos of Māori people or places, including the natural environment.

Māori Tattoo’s/Tā moko, Moko Kauae

There is a resurgence of the art of Māori tattoo’s being worn by Māori adults on their body called Tā Moko. Facial tattoos are called a Mataora and for women on their lips and chin the tattoo is called a moko kauae. The styles and the artwork represent a story unique to the individual and often recognises genealogy, life achievements or other unique and personal stories to the wearer and their family.

It is inappropriate to copy another persons Māori designed tattoo or to copy it and make modifications. This rule applies to the living and deceased no matter how old the image is.

Creating a unique Māori tattoo and applying it to your brand, game character or product will likely be offensive and should be avoided at all times.

Māori Flags

On 14 December 2009, Cabinet recognised the Māori (Tino Rangatiratanga) flag as the preferred national Māori flag. The national Māori flag was developed by members of the group Te Kawariki in 1989. On 6 February 1990, the group unveiled the flag at Waitangi.

While a number of people have claimed ownership and/or rights to the flag, the flag does not belong to any one Individual, whānau, Iwi, Company, Organisation, Religion or Political Party.

The collective who created the flag did ask for the following to be respected with the flag.

- Don’t change the dimensions or colours – it loses its essence

- Don’t wear it around your waist

- The symbol can be used for any kaupapa that promotes, encourages and supports Te Ao Māori and should not be used or sold for personal gain.

It is also important to not display the flag upside down.

There is also another flag that is often used to promote Māori. It is often called the United Tribes Flag. There are two versions of the flag. One that was designed by and accepted by the majority of Māori society. Then there a slight variation that was designed and approved by non Māori.

The appropriate flag has the black boarder around the four stars as seen below.

Photos

Do not produce or share photos of Māori individuals, groups or of any crafts, carvings, taonga etc without consulting and then be prepared to provide context, tribal identities, and ideally names too (unless asked not to).

If the image is of an historical deceased person, seek permission from the family.

Taonga Species/Indigenous and Native Species

In Māori culture every natural object and Native and Indigenous species (Taonga Species) has traditional knowledge associated with it. Each Taonga Species and natural object has a genealogy and a story of creation. Many Taonga species and objects are used for rituals, medicines, personify something or are a guardian to some Iwi.

Careful consideration of using a Taonga Species, including names in a product or brand requires research and consultation about the purpose of the species or natural object in Māori society. It is increasingly becoming acceptable for the Kiwi to be used without any cultural considerations.

It has recently become popular to wear a plastic or other imitation of the extinct Huia bird feather. The Huia feather was traditionally only worn by chiefs and people of high importance. Then the royal family and other European settlers wanted the feathers as an accessory leading to the extinction of the bird. For Māori, the imitation feathers could be seen as a sign of promoting colonisation.

The Fantail is another common taonga species that is used in products and branding, yet it has a complex system of knowledge and in some instances is associated with death.

Te Reo Māori/The Māori Language

The Māori Language is an official language of New Zealand recognised by The Maori Language Act 1987/ Te Ture Reo Māori 2016. In addition to the legislation, the Māori Language has been recognised by the Waitangi Tribunal as a Taonga. The Māori language is for all New Zealanders, not just Māori. But there needs to be caution when using Māori language.

Current best practice for spelling and writing Māori is contained in Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori Guidelines for Māori Language Orthography downloadable from https://www.tetaurawhiri.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Corporate-docs/Orthographic-conventions/58e52e80e9/Guidelines-for-Maori-Language-Orthography.pdf .

Māori to English translation

A Māori word is likely to have multiple meanings and some words have significant cultural value. If using a Māori word, you should be aware of the meaning and cross check multiple Māori dictionaries and ensure that your image matches the Māori word and has a whakapapa/story.

A macron is placed above a vowel to indicate that the sound is longer than the other vowels. If a macron is not added to a word, it can change the meaning of the word.

Some Māori words and concepts can be translated into English without causing offence. However, sometimes there’s another layer of meaning or understanding that needs to be considered. For example, the word ‘matua’ could be translated as ‘parent’. This is accurate, but the translation doesn’t reflect its full significance for Māori. In Māoridom, matua is a term used to show great respect — recognising a person’s achievements, wisdom and contribution, usually a male. In this light, it would be offensive for matua (tapu) to be associated with things like food and alcohol (noa).

Like any specialty, just because someone can speak Māori does not make them a Māori language expert. The most appropriate Māori language experts are licensed Translators and Interpreters. Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori/The Māori Language Commission was set up under the Māori Language Act 1987 and continued under Te Ture Reo Māori 2016 | Māori Language Act 2016 to promote the use of Māori as a living language and as an ordinary means of communication. As one of their roles, they manage the National Translators’ and Interpreters’ Register, a register of certified high-level, translation and interpretation skills experts. The register is available at https://www.tetaurawhiri.govt.nz/en/services/national-translators-and-interpreters-register/

When considering using a Māori word or phrase it is important to consult a number of authoritative Māori language resources and in some cases a Māori language expert. There are several Māori Language Dictionaries online including:

| Te Aka Māori Dictionary | https://maoridictionary.co.nz/ | A general all-purpose dictionary. |

| Ngata Māori Dictionary | https://www.teaching.co.nz/dictionary | Macrons are not used on common words. |

| A Dictionary of The Maori Language | http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WillDict.html | Traditional words and no modern vocabulary. |

| Index of Māori Names | https://www.waikato.ac.nz/library/resources/digital-collections/index-of-maori-names/ | Names and their associations. A good reference for seeking if a name is sensitive. |

| Dictionary of Māori Computer and Social Media terms | https://www.taiuru.co.nz/dictionary-computer-social-media/ | Only technical terms associated with computers and the Internet. |

Māori names

As a general rule, any use of a personal names are problematic and should be avoided. The exceptions to this rule is the use of modern Māori names that have been transliterated. These names are usually Christian names or names that have been made up to give a person a Māori version of their name. A detailed list of these names is available at https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-baby-names-list/

Iwi, marae and other traditional collective names should never be used outside of the collective.

Māori geographical names such as Taranaki all have significant meanings and associations to the local iwi and Māori. It is recommended to talk to the local Iwi if using geographical names.

Māori deity names are likely to be offensive and should not be used without consultation and engagement of an expert.

Haka

The New Zealand Rugby team the All Blacks have made one Haka, Ka Mate famous across the world. Attempts at the haka by people all over the world including drunk New Zealanders in England, American sports teams, celebrities, and UK nurses have caused widespread offence.

The Ka Mate Haka is protected by legislation in New Zealand and requires attribution to Ngāti Toa. If using any haka, you should learn the history of the haka and seek professional assistance to perform it.

Some would be horrified at the true meaning of haka and especially the Ka Mate Haka. Applying black paint and mock Māori tattoo’s to you face and other attempts to appear Māori are likely to have the opposite effect and are likened to the Black Face offence.

Applying for a Trademark that has a Māori Element

If you apply for a TradeMark in New Zealand that contains a Maori cultural element or Indigenous Species of New Zealand (Taonga Species), then it will be reviewed by the Intellectual Property Office – Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee.

The role of the committee is not to tell you if you application is incorrect or could be viewed in different perspectives by various Māori sectors in the community. The role of the Māori Advisory Committee is to decide if your application will be offensive to a large sector of Māori. If it is offensive, then your TradeMark can be declined.

If applying to TradeMark your brand, you should still seek appropriate independent expert advise.

.nz Domain Names

Most business and brand owners have an online presence and usually a New Zealand entity uses a .nz domain name that identifies the entity and product being a New Zealand product.

New Zealand and the United States of America have pre identification domain names for their Indigenous Peoples. In New Zealand there are three options for Māori and tribal entities and products to be represented:

- .maori

- .māori.nz

- .iwi.nz

The maori.nz domain with a macron is a default option for any registered maori.nz domain. It requires some technical changes to operate. Dot maori.nz is available for anyone in the world to identify their entity or product as Māori and create their online presence. The principle of the domain name was based on New Zealand legislation that anyone person can state they are Māori if they have a Māori descendant.

If you are protecting your brand and registering in all of the .nz options, also using Dot maori.nz is acceptable.

Dot iwi.nz is moderated and for exclusive use of Iwi of New Zealand. This provides Iwi with the exclusive online branding of trust and authenticity.

Within the .nz domain name space is a disputes process. If you are using a Māori name for your online presence, you should consult and check that the name is not offensive.

Appendices

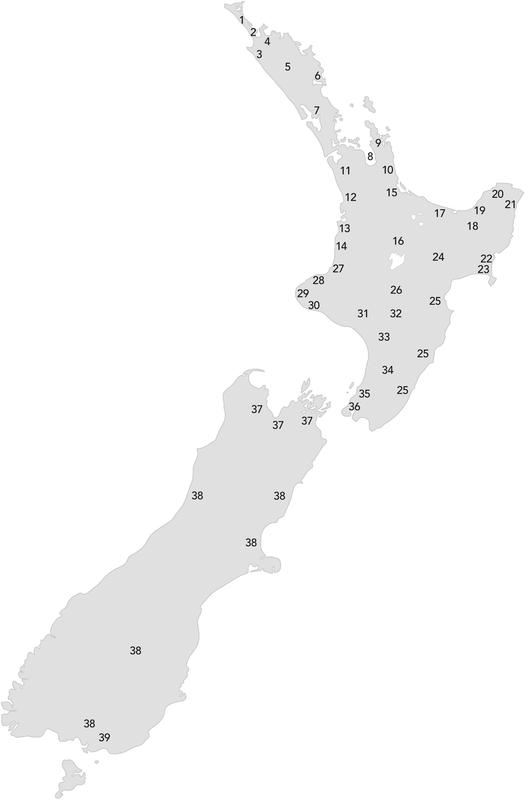

Appendix 1 Iwi locations, 2001

The map (Source: Statistics New Zealand, New Zealand Official Yearbook 2002) provides an approximate indication of where iwi are located. Iwi include those who have 1,000 or more affiliate responses, based on the 2001 Census of Population and Dwellings. Responses may include identification with more than one iwi.

- Ngati Kuri

- Te Aupouri

- Te Rarawa

- Ngati Kahu

- Nga Puhi

- Ngati Wai

- Ngati Whatua

- Ngati Paoa

- Ngati Whanaunga

- Ngati Tamatera/Ngati Maru

- Ngati Haua (Waikato)

- Waikato

- Ngati Raukawa (Waikato)

- Ngati Maniapoto

- Ngati Ranginui/Ngai Te Rangi

- Te Arawa

- Ngati Awa

- Whakatohea

- Ngai Tai

- Whanau-a-Apanui

- Ngati Porou

- Rongowhakaata/Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki/Ngai Tamanuhiri

- Rongomaiwahine

- Tuhoe

- Ngati Kahungunu

- Ngati Tuwharetoa

- Ngati Mutunga

- Te Ati Awa (Taranaki)

- Taranaki

- Nga Ruahine/Ngati Ruanui

- Te Ati Haunui-a-Paparangi

- Ngati Raukawa (Horowhenua/Manawatu)

- Ngati Apa (Rangitikei)

- Rangitane (Manawatu)

- Muaupoko

- Ngati Toa Rangatira/Te Ati Awa (Whanganui-a-Tara)

- Te Ati Awa (Te Waipounamu)/Ngati Rarua/Ngati Koata/Ngati Kuia

- Ngai Tahu/Kai Tahu.

Leave a Reply